- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

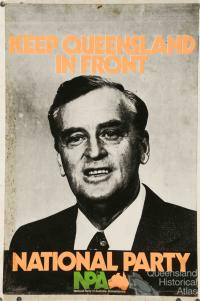

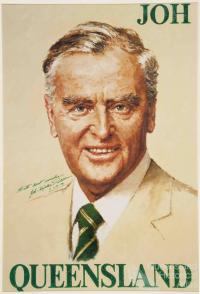

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

Sean Ulm

By:

Geraldine Mate Conflict is fundamental in shaping the Queensland landscape. When Coonowrin failed to take his pregnant mother Beerwah and brothers and sisters to safety during a storm his father, Tibrogargan, broke his neck with a club. Tibrogargan was so ashamed of his son that to this day he sits with his back to Coonowrin, creating what is commonly known as the Glasshouse Mountains. Beerwah remains there too, heavy with child, her tears forming the creeks running out to sea.

In the Gulf of Carpentaria, the Dugong River which dissects Mornington Island was created after Bulthuku burnt down her brother Thuwathu's wet weather shelter. Thuwathu had repeatedly refused to let Bulthuku and her child take shelter inside during the rain. The child died from the cold and in her rage Bulthuku set fire to the shelter. Thuwathu, the Rainbow Serpent, was badly burned and his death throes created the river as he writhed in agony across the landscape.

About conflict and landscape

Landscapes are always tensioned, nourishing and sustaining multiple meanings and perspectives. The contours of tensioned landscapes are formed by conflict – over resources, worldviews, ideologies – woven into the very fabric of the land through the entanglement of people and place. Conflict in the landscape can work at multiple levels and scales and rarely involves physical violence per se. War cenotaphs and memorials, for example, insert conflicts into landscapes from other times in distant lands. These form the focus for reflection, grief, pride and protest expressed on occasions like Anzac Day and Remembrance Day. That is not to say that violent conflict has not been written into Queensland landscapes, such as the shooting and drowning of 300 Aboriginal men, women and children at Goulbolba Hill in Central Queensland in 1876 or the Japanese torpedoing of the Centaur off Moreton Island in 1943 with the loss of over 250 women and men. But conflict is also enfolded in the landscape in other ways that we might not immediately recognise. There is contestation over the very remains of people in the landscape, evident in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander demands to repatriate ancestral remains removed from cultural places, and public outrage at the desecration of graves during the widening of Hale Street in Brisbane in the 1990s. At the other end of the spectrum, conflict over drinking rights ranges from actor Sigrid Thornton’s mother Merle chaining herself to the bar of the Regatta Hotel in Toowong, Brisbane, in 1965 to demand the right of women to drink in public bars, to riots against restrictions imposed by Alcohol Management Plans in north Queensland Indigenous communities.

The way we act and move in landscapes when we engage in conflict (for example street marches, violence, storytelling) is not the same as how we act in landscapes shaped by conflict (for example when we grieve at massacre sites or war memorials). Conflict landscapes are therefore contoured by the meanings we create through the events that take / have taken / will take place there, our personal and collective engagements with them and the worldviews and knowledges we bring to them. Some landscapes bring highly emotional responses, while others might only give some of us pause for reflection as we move through them. Expanses of devegetated and depeopled pastoral holdings encode long-term conflicts over Indigenous ownership and possession with marked boundaries symbolic of the dispossession of Aboriginal people. The cleared spaces of these lands reflect a contest over the wilderness undertaken by settlers that demonstrate the dichotomous environmental values of Aboriginal people and settlers. To those passing through these landscapes without intimate knowledge of the pastoral landscape this may bring some reflection but little of the emotional response in comparison to that felt by Traditional Owners whose view of fences and cleared land might be far more visceral and emotive.

In these ways, conflict is central in producing meaning in the landscape. The changeable quality of landscape provides spaces for resilience and reconciliation, suppression and celebration, remembrance and grief, and potential for supporting competing stories about the landscape.

Creating conflict in the landscape

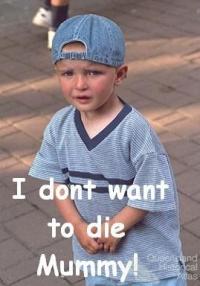

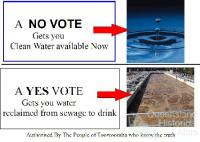

Contestation about resources and different views of what is important are the stage for conflict in the landscape. The Traveston Crossing Dam became the focus for conflict over resources and ideologies of environmental groups, Aboriginal Traditional Owners, farmers and the State Government. The proposed dam would have transformed farmland into a large freshwater lake, forcing farmers and other residents off the land, submerging important cultural places and changing the environment for rare species such as the lungfish cod and Mary River turtle. During a period of extreme and prolonged drought, the State Government argued that the dam was crucial to water security in a rapidly urbanising part of the State. This vocal dispute was marked on the landscape with signs proliferating along the Bruce Highway, documenting the deeply-held feelings of the protesters (‘Don’t Murray The Mary’ is one of the more memorable). Other such examples include the well-orchestrated campaign against the introduction of recycled water in Toowoomba (with the slogan ‘NO to putting POO in TOOwoomba’s Water’), or ongoing conflicts over sandmining on North Stradbroke Island, coal seam gas in central and western Queensland and lead levels at Mount Isa.

A long history of development at odds with local community opinion is an ongoing source of conflict in Queensland as disputes over developments like the Iwasaki resort, the Cairns Skyrail and Mount Etna proclaim. The bombing of the Iwasaki resort at Yeppoon in 1980 highlighted an intersection of political and environmental conflict when the ‘Queensland beautiful one day Japanese the next’ agitators against the Bjelke-Petersen Government approach to foreign investment formed an unlikely alliance with local environmental lobbyists to protest construction of the resort. The Bjelke-Petersen era was one of extended political conflict with street march crack downs, extensive powers for the Special Branch, and restrictions on freedom of expression. The demolition of the Belle Vue Hotel and Cloudland Ballroom in Brisbane forever changed the heritage landscape of Queensland, sparking demands for heritage conservation and legislation.

The SEQEB strikes of the early 1980s are another long remembered feature of that era. From these contestations, it is apparent that labour itself has been a source of conflict through the history of Queensland – from the shearer’s strike of the 1890s, through trade unionism and the politics of labour in places like Rockhampton and Mount Isa to modern discord over industrial relations laws. Much of the conflict has its naissance in access to resources – access to land as a resource, and the use of labour both to extract resources (mineral, agricultural) and as an expendable, de-humanised resource. Blackbirding, the coercion of South Sea Islanders onto boats and into semi-slavery conditions on the cane fields of Queensland, is one such conflict. The long low stone walls built by South Sea Islanders that stretch across paddocks along the Queensland coast are a marker of the exploitation of these people in the sugar industry.

Conflict for South Sea Islanders continued with their forcible deportation under the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901. Previous legislation had also limited the freedoms of Chinese, particularly on the goldfields. Although originally welcomed as a means of solving labour shortage problems at the end of convict transportation, Chinese people quickly came to be regarded as a threat. High public agitation, particularly in the context of gold mining, led to repressive legislation that restricted many aspects of their lives. Conflict extended to physical violence with rioting on the goldfields. The anti-Chinese sentiment reached a peak during elections in 1888. Approximately 1000 agitators rampaged through the Brisbane Chinese quarter, smashing shop windows, once again writing conflict on the landscape.

European invasion of Aboriginal lands was a constant source of conflict on the expanding Queensland frontier. In the nineteenth century the feared Native Mounted Police routinely conducted ‘dispersals’ throughout Queensland. Charles Arthur’s eyewitness account of one such instance reports that Aboriginal people in the Port Curtis district directed several attacks in quick succession against McCabe’s surveying party in 1854. Reprisals were carried out by the Native Mounted Police under Lieutenant Murray following soon afterwards:

Mr Murray and the police returned about 1 P.m – They fell in with the blacks yesterday evening and they got on them … They surrounded them in a scrub and I believe (as Mr Murray says) that only one out of (22) twenty two got away to tell the tale – so that altogether they have shot dead 23 Blacks concerning this robbery of our camp and perhaps may have wounded some more when the first two were shot near the Camp – I think this will check the Darkies a little – most of the property was got again. The blacks fought for a while most determinedly.

The screams of the maimed and dying after violent clashes on the frontier are muted in secondary accounts of frontier conflict. These accounts promote the idea that conflict is somehow enfolded in a distanced national past that has little contemporary resonance. Such approaches sanitise the past in distancing us from the emotion, horror, personal impact and the costs of conflict. European encroachment onto Aboriginal lands continues apace today with the expanding frontiers of residential development and mineral exploration and exploitation, with conflicts played out on the ground, in the media and in the courts.

Politicising conflict in Queensland landscapes

Today the land is divided, carved up with fences and roads, the scars of contestation of land, with exclusion of Aboriginal people from their lands and cultural places continuing. The battles over land rights and Native Title, inscribed on the political landscape by both the Mabo and the Wik decisions, show that conflict still surrounds the earliest colonial approach to taking and distributing land claimed by the British Crown. The politicisation of conflict, segregation and policing of the colonial era provide the underpinnings of other elements of Queensland’s conflict landscapes, such as Aboriginal deaths in custody which continue at high rates today, and the continuing low rates of Indigenous people represented in employment and education and over-representation in detention.

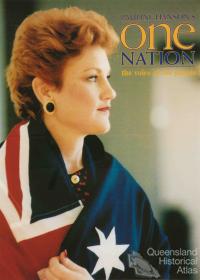

During Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s long premiership (1968-87) Queensland came to be regarded, especially in southern states, as the Deep North, with draconian restrictions placed on the rights of Indigenous Queenslanders and others. More recently, the rise of Hansonism and One Nation demonstrated the extent of racism in parts of the Queensland community. Pauline Hanson and her party ran on a thinly veiled platform of race and economic protectionism that failed to acknowledge a long and sordid conflict history. Hanson's maiden speech in Federal Parliament on 10 September 1996 outlined her core agenda:

I have done research on benefits available only to Aboriginals and challenge anyone to tell me how Aboriginals are disadvantaged when they can obtain three and five per cent housing loans denied to non-Aboriginals.

I am fed up with being told, `This is our land.’ Well, where the hell do I go? I was born here, and so were my parents and children.

I believe we are in danger of being swamped by Asians.

A truly multicultural country can never be strong or united.

In the Federal Election of March 1996 Hanson, running for the seat of Oxley in south Brisbane, recorded the largest swing against the Keating Labor government of that election – 19.3%. Less than two years later, in 1998, the newly formed One Nation Party pulled in a primary vote of 22.7% in the Queensland State election. This amply demonstrates how divided mainstream Australia remains over questions of racial conflict and Aboriginal rights.

Negotiation, reconciliation, resilience

Conflict is written in the landscape and is ever-present in the way we negotiate meaning. Engaging in conflict can be productive, even creative. In the case of sandmining on North Stradbroke Island, for example, the continuing conflict through the 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s has led to a belated recognition of the value of the cultural and natural landscapes and the gradual phasing out of mining on the island as the mining leases expire.

Landscapes do not unfold before us as we move through them. Rather landscapes come into being precisely because we engage with them – collectively and individually – and they enfold us in themselves. The performance of conflict – in violence, in protest, in stories and in grief – animates these landscapes.

Returning to Mornington Island, Lardil people believe in a fundamental conflict between things from the sea and things from the land. Thuwathu, the Rainbow Serpent, inflicts an illness known as markirii on those who are careless in mixing things from the land and sea. As Thuwathu lives in the sea he controls all things touched by seawater, making the coastal zone a particularly dangerous place. Great care must be taken in negotiating this conflict between sea and land, just as all negotiation of conflict must be mediated in its context.

References and Further reading (Note):

C. Arthur, ‘Private journal of Charles Arthur (MacCabe’s Assistant Surveyor and Draftsman), 1853-1854’, nd

References and Further reading (Note):

H. Chan, A. Curthoys and N. Chiang (eds) The overseas Chinese in Australasia: history settlement and interactions, Canberra, Centre for the Study of the Chinese Southern Diaspora, 2001

References and Further reading (Note):

R. Evans, K. Saunders and K. Cronin, Race relations in colonial Queensland, St Lucia, University of Queensland Press, 1988

References and Further reading (Note):

R. Gibson, Seven versions of an Australian badland, St Lucia, University of Queensland Press, 2008

References and Further reading (Note):

R.D. Goodman, Hospital ships, Brisbane, Boolarong Publications, 1992

References and Further reading (Note):

P. Memmott, ‘Rainbows, story places, and malkri sickness in the north Wellesley Islands’, Oceania 53/2, 1982

References and Further reading (Note):

N. Richards (comp), Leerdil Yuujmen Ngalu: Lardil traditional stories, Cambridge, MA, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, nd