- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

Luke Keogh The Brisbane River floods. In the extreme episodes of natural disasters a boatload of stories flow from the mouths of people to comprehend their landscape. Radio, television and the internet provide up-to-date reports on the state of the weather, while the print media plays an important role in communicating stories after the event and influencing the perceptions of floods by the community. Placing the Brisbane floods in a broader environmental and historical context, this article is about the print media’s mapping of the Brisbane floods in 1974 and 2011.

‘It was worse in 1893’

As the floodwaters reached their peak of 5.5 metres at the city gauge in the early morning of 29 January 1974 the Courier Mail was running off prints of the day’s newspaper to be circulated to concerned Queenslanders and Australians. The front page headline read ‘Rescue disaster as floods hit new top: city almost at standstill’. And next to the text an aerial image looking down Coronation Drive toward the city showed the ‘flood devastation in Brisbane’.

As the floodwaters slowly subsided, turning to page four of the same edition of the paper, the wake brought a sense of history. Douglas Rose commenced his article ‘It was worse in 1893’ with the shock of the present flood and its context compared to previous floods: ‘Extensive and shattering as the havoc of south-east Queensland’s present flood is, the disaster still has not quite matched the torrential fury of the 1893 flood.’ Rose went on to discuss the horror of the 1893 flood. He noted:

with such graphic reports of the Great Flood of ’93 – still the yardstick for measuring Brisbane’s water damage – in the records it seems remarkable that the lessons of that time often still have not been acted upon. There have been repeated warnings that something similar could happen – as it has.

Rose took his authority from bureau meteorologists and university engineers who had warned in the previous decade that a flood the size of 1893 could happen again. Civil engineer G.F. McKay from the University of Queensland said, ‘Nothing has changed much … The situation today in conditions like those of 1893 could be far worse because of the high density building around creeks in Brisbane.’ Rose took a longer historical perspective noting ‘what needs to be borne in mind too is that the 1893 flood was NOT the all-time record flood for the area.’ History not only contextualised the 1974 flood, but for Rose, like many other commentators voicing their concerns in the backwash, complacency of planners played its part in the catastrophe of the event.

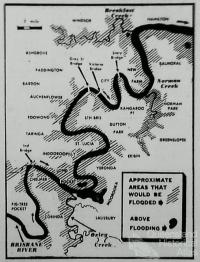

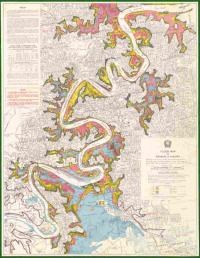

The subheading concluding Rose’s article told readers, ‘We were warned’, and here maps showing possible flooding along the Brisbane River played a significant role. The article reproduced a map from the March 1953 edition of the Courier with the new title ‘Warning 21 years ago’ and showed the areas that would be inundated if large-scale flooding occurred in the Brisbane River – areas at that moment underwater. Looking from the 1953 map to his experiences of the present flood, Rose concluded: ‘Although the extent of the present floods have still to be mapped accurately, there seems to be a large area of agreement between the area affected by the 1953 warning and the present submerged districts.’

‘Somerset Dam won’t save Brisbane’

The article Douglas Rose drew his map from was ‘Somerset Dam won’t save Brisbane’ an article by H.W. Herbert that appeared in the Courier Mail on 2 March 1953.

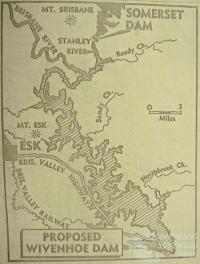

In the summer of 1953 southeast Queensland experienced steady rain. February was the wettest since 1934 and on 26 February Brisbane got 75 points in twelve minutes from a large black storm cloud that, as shown on page one of the Courier Mail, hung over the city like an apocalyptic omen. By 2 March an aerial image of Somerset Dam, on the Stanley River in the upper Brisbane River catchment, ‘at the height of the floods’ appeared in the paper. The image was captured by staff reporter Cliff Potter from an Australian National Airways flight returning from a supply-dropping mission in the flooded western Queensland: ‘Dam traps 60,000 million gallons’ the large title told readers. The quantity of water held back by the dam trapped a year’s supply of water for Brisbane. But at that stage the dam was unfinished: ‘Stacked on top of the dam was equipment being used to raise the height of the eight spillways a further 23 feet for flood control’ creating an even higher dam wall to prevent further flooding.

Paradoxically, turning from page three to four of the same edition of the Courier Mail, saw an image taken of the dam by a reporter returning from flooded western Queensland, met with the bold headline: ‘Somerset Dam won’t save Brisbane’.

‘Just because Somerset Dam saved Brisbane from flooding during the recent heavy rains this is no time to sit back and say “Brisbane will never have another serious flood,”’ commenced H.W. Herbert in his cautionary essay. Herbert had made a study of the Brisbane River flood risks when he was a staff member of the Bureau of Industry and clearly noted that the designers of Somerset Dam never claimed it would do more than take the top ten feet of a major flood.

Commenced in the 1930s and completed in 1953, Somerset Dam backed up the waters of the Stanley River which flowed into the upper Brisbane River. The dam was named after H.P. Somerset who had pointed out the suitability of the dam’s location in 1906. Somerset, the man, was well known for warning of a huge ‘wall of water’ from the Stanley River heading for Brisbane in the first of the 1893 flood events. His warning was ignored by many, including newspapers, but in the second flood event of 1893 he had stockman Billy Mateer ride on horseback to North Pine to successfully deliver the warning. In a letter to the Courier Mail on 16 November 1935, Somerset clarified for misinformed reporters that the reason the town and dam bore his name were for his understanding of the landscape. ‘The reason is that in 1906, when the old Water Board proposed to utilize the lake on Stradbroke Island for Brisbane water supply, I wrote suggesting they send an Engineer to inspect the site on the Stanley River, which I said would answer for supply of good water, and also for flood mitigation.’ At the time it was a practical choice over a dam at Middle Creek further down the catchment. By 1953 when the dam was nearing completion, Herbert described it as a ‘bargain’ because it utilised cheap labour in the 1930s as well as having natural rock formations suitable for dam construction.

W.H.R. Nimmo, Commissioner of Irrigation and Water Supply and one of the designers of the Dam, claimed that geological evidence and native legend indicated bigger floods before white settlement. Following a discussion of the 1893 flood, Herbert estimated that a flood of that size would cause $1 million worth of damage, whereas a minor flood of 1931 or 1950 type would hardly be perceived by residents in Brisbane. He understood that a big flood was possible and thus, ‘the indiscriminate building of houses and industrial buildings in low-lying sites should be discouraged.’

In 1953, the south-east experienced heavy rain, a good test of the Somerset Dam, nearing completion. Herbert’s knowledge of the river also told him that the wider public were out of step with the environment they inhabited. He concluded, ‘Twenty years without a minor flood and sixty years without a major flood, plus a mistaken idea of the power of the dam, have made the flood risk in Brisbane seem less than it probably is.’

The early 1950s saw four floods exceeding 2.74 metres in height (at the Port Office). The highest occurred on 27-28 March 1955 with the Stanley River receiving thirty-per cent of the rainfall. The water was held back by the recently completed flood mitigation measures of Somerset Dam and was released once the waters from the Brisbane and Bremer Rivers had flushed out to sea. Tried and tested, the dam pulled through. But again there were warnings.

As well as Somerset other flood control measures had also taken place, in particular dredging and the build-up of banks. However, the Courier Mail reported on 29 March 1955, ‘the Brisbane River alone is capable of causing serious flooding in Brisbane, and the Somerset Dam could not stop this.’ And two days later the paper reported that after the flood the Brisbane City Council had mapped the flood areas ‘with the object of preventing further residential development there’.

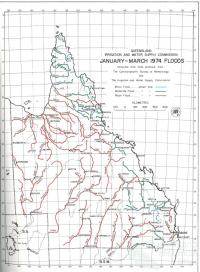

‘Highest since 1955’

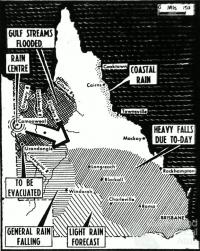

On 26 January 1974 papers reported that Brisbane had become ‘a city of island suburbs’. The river was at 3.5 metres and lapping at the 1955 level of 3.6 metres at the Port Office. Brisbane received 168 mm in twelve hours and the papers reported Weather Bureau director A.J. Shields as saying: ‘The rain was so heavy over such a wide area that flooding occurred in almost every water course.’ Water entered the Cabinet room and the Premier’s office in the high-rise Executive Building, week-end sport was cancelled, and the postal service could not deliver mail to many Brisbane suburbs. The front page was still reporting the flood crisis in Normanton. Maps on the front page showed the ‘Deluge at a glance’ with floods across the State. The map of south-east Queensland showed cyclone Wanda on a pathway towards Brisbane.

‘It was Brisbane’s Dunkirk’

The battle against the ‘Great Flood’ in Brisbane commenced early on Australia Day 1974. The flood crisis spread across the State, from Normanton to Brisbane. In the Gulf country it had already reached the level of national disaster and Member for Kennedy Bob Katter estimated over $100 million in damage for the north. On the Gold Coast 2000 people were evacuated as the Nerang and Logan Rivers broke their banks. In Ipswich the swelling Bremer River and other creeks caused the evacuation of 1000 people. In Brisbane, 314 mm fell, to make the wettest day in 87 years, causing 4000 people to be evacuated from homes as ‘the worst flood in memory turned Queensland into a sea of mud and water yesterday.’ The Army and Air Force were called in to help police evacuations: ‘RAAF Iroquois helicopters flew mercy missions in the metropolitan area’. Defence aircraft including planes and helicopters allowed not only the Premier but also reporters and photographers to view the damage from the air. Looking from the air they called the flood ‘the biggest ever in Brisbane’. The Courier Mail on 27 January 1974 described the extent of evacuations, with typical hyperbole, as ‘Brisbane’s Dunkirk’.

‘When water runs wild’

As the maps in the papers predicted, tropical cyclone Wanda passed over Brisbane on the Australian Day long weekend. From 25 to 27 January, 580 mm of rain was deposited on the capital, with some areas such as Mt Glorious receiving over 1300 mm.

As ‘Wanda’s flood hit Brisbane’ radio and television communicated this to the public. Enoggera Creek broke its banks and took with it four houses and flattened grasses and shrubs, one hundred caravans were swept down Woogaroo Creek, commuters in Brisbane were without buses, umbrellas were abandoned in litter bins as no defense against the cyclonic activity, streets became canals and people moored boats to verandahs. In huge seas the ‘To and Fro’, a 14-metre sloop, ran aground on North Stradbroke and the four people inside were saved by sand-miners. The shallow Oxley Creek spread out over Rocklea market and Sherwood Road and debris floated down Breakfast Creek and broke up against its bridge. Sightseers got in the way of rescue efforts.

Even as all this drama appeared in news stories it took until page six of the 28 January edition of the Courier Mail, the day the flood was due to peak, to get a proper weather report.

The stories continued. A gravel barge collided with the Centenary Highway Bridge and had to be sunk with dynamite. The Robert E Miller, a huge tanker, attracted photographers as it broke its moorings near the Story Bridge and desperate efforts had to be taken to secure it. Drums of highly explosive material washed out of a Moorooka factory built in a flood prone area and were spotted in New Farm. Looters travelled down Fairfield Road in a boat. Sunday drinkers arriving by surf ski watched on from the balcony of the Regatta Hotel. Paul’s Milk factory in South Brisbane, which supplied milk to most of Queensland, flooded and a major milk shortage ensued. Hero stories began to emerge: people like Ray Haslam who spent day and night in a dinghy travelling through murky Indooroopilly floodwaters saving people and their possessions.

The front page of the 28 January Courier Mail reported ‘Crisis to last for days: city’s flood fighters weary’. One third of the police force had to stand down to conserve the energy of workers as the Police Commissioner Ray Whitrod told papers: ‘many officers were suffering from fatigue from the endless rescue operations.’ He went on: ‘The force has been stretched to its utmost … If we’d known this situation was going to last more than seventy-two hours, we’d have conserved forces earlier.’

‘Rescue disaster as floods hit new top’

In Kenmore, two services personnel were killed, one instantly and one washed away, when their LARC army amphibious vehicle hit high tension wires. A survivor said after the event, ‘The whole craft was electrified. People were moaning and screaming and there were sheets of flame and a sound of an explosion.’ In total fourteen people lost their lives in the flood events of January 1974.

On 29 January 1974, papers reported on the major tragedy of the army rescuers as the flood reached 5.5 metres at the city gauge. ‘The flood virtually paralysed the city, cutting most major roads and badly damaging scores of others. The city’s commuters face a grim task this morning getting to work’. There were fears of food shortages as many low lying warehouses were swamped by water. Overall, it was described as, ‘The worst floods in a century’. It started being called the Great Flood.

The 29 January edition of the Courier Mail ran Douglas Rose’s article, ‘It was worse in 1893’. Hindsight, and its close ally blame, accumulated in the receding waters, like mud shoveled into a bucket, as the community and reporters looked for answers – looked for someone or something to blame.

‘The guns are out at Jindalee’

‘We all thought 1893 wouldn’t happen again because of Somerset’ one Hooker Centenary property developer told Channel 7 news reporters after the floods had ravaged the new housing estates in Brisbane’s western corridor. With the previous minor floods and the moderate flood of 1955 held back by the dam, perceptions of the Brisbane River had changed and few understood that the dam did not hold back water in ninety-per cent of the catchment, as was correctly reported in the press.

In the editorial of 28 January 1974 the Courier Mail suggested, ‘These floods demonstrated that while Somerset Dam provided some control over water levels in the Brisbane River, it was by no means a complete answer to severe flooding of Brisbane. The city’s creeks were another problem’. The editor concluded succinctly, ‘the lesson has surely been learned the hard way’. As the flood waters subsided, what lessons were there to be learnt?

On 30 January 1974 the headline of the Courier Mail fuelled the community’s need for answers by running a lead article on the flood-isolated new suburb of Jindalee. The lead image presented to readers Jindalee resident Graham Grice carrying a .418 rifle with two youths standing next to him sharing a .22 rifle. The armed vigilantes were ready to fend off looters from their property on Kangaloon Street. In Jindalee, there were reports of looting and black market trades in bread, milk and cigarettes, and local residents had set up a check point at the entrance to the suburb to monitor people coming and going. (The following day the Courier Mail reported a legal expert that suggested the armed vigilantes could face life imprisonment if they shot anyone for looting.)

The new middle-class suburban development of Jindalee provided an exemplary case study for reporters. The unregulated development of floodplains, largely blamed on legislators and opportunistic developers, were high on the list of those who had exacerbated a devastated Brisbane.

After federal science minister Bill Morrison surveyed the floods, papers reported on 28 January 1974 that federal assistance would be made available to flood victims. Flying high above in the RAAF Iroquois helicopter he was compelled to make conclusions. ‘But I must say that many of the flooded areas have been zoned irresponsibility [sic] for housing and industrial development’. After taking into account the testimony of people he met in Brisbane, he went on:

zoning is a State responsibility and they will have to give local government power to execute responsible zoning. In some cases natural water courses were filled in, homes or factories were built too close to the river or in areas where flooding occurs regularly. One man told me he had been flooded out seven times in nine years. That is ridiculous. The area never should have been zoned for housing.

Many people told Morrison that because they were in flood areas they couldn’t get insurance – they had nothing. So if they couldn’t get insurance, how did areas get zoned for housing?

As early as 27 January 1974, the Federal ALP vice president Jack Egerton was calling for all flood areas to be resumed by the State Government and turned into parks. He argued that people should be resettled to prevent the ‘same sort of flood chaos happening again’. For Egerton the lack of authority given to the Brisbane City Council to stop building was a key problem. He said, ‘What happened now will happen again and no flood mitigation scheme will stop it. The Government has to give the City Council power to stop building on danger areas’. A few days later, the comments of Egerton, given a large space on page five of the Courier Mail, were heavily criticised by developers.

The flood was a ‘freak of nature’, claimed the State President of the Urban Development Institute of Australia W.H. Bowden in a letter to the editor of the Courier Mail on 1 February 1974. The urban development industry was ‘shattered’ that news media could afford to devote space in the flood crisis to the accusations against them, particularly those of Egerton. For the urban development industry, ‘development of Brisbane has proceeded on the calculated reasoning of capable professionals that the 1893 floods would never happen again.’ Such claims were largely based on the misplaced belief or scapegoat that Somerset dam would prevent major floods in the future. On top of this, Bowden argued that if development was restarted from the beginning of the century again, no matter which level of government or even private developers, had authority for the areas the same pattern of subdivision would occur again. To urban developers what were now floodplains from the recent flood were not always so, and the industry could not be held to blame for what was, he repeated, a ‘freak of nature’.

It appeared hard to heed Bowden’s call when graphic representations in the papers showed ‘watery invasions’ of Jindalee and ‘water covers luxury houses in St Lucia’. But not everyone succumbed to doomsday predictions. University students refused to be evacuated from their St Lucia residencies and hung banners from their balconies telling of the new ‘St Lucia canal estate’. Or when residents of Cromarty Street in Kenmore placed a for sale sign outside their home that read ‘For Sale. Price 1 Doz. XXXX & A Clean Glass. Features: holds 788,000. Gal, no fridge and dirty pool. Cheer up those still under – we-re still alive. PS. I wouldn’t sell anyway – the neighbours are too good to move away from.’

‘Brisbane bids for Games’

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam didn’t return to Australia to offer support for the flood victims in Queensland. From Kuala Lumpur on his Asian tour, Whitlam phoned the Brisbane Mayor Clem Jones to ‘express his deep concern at Brisbane’s flood tragedy’. Whitlam had travelled to Asia after attending the opening of the Commonwealth Games in Christchurch. Australia’s first gold at those Games was from Sonia Gray when she won the 100 metres freestyle in 59.13 seconds on 25 January. Days later athlete Margaret Ramsay would ask to be released from sporting commitments so that she could return to her flooded family in Ipswich. The Brisbane Lord Mayor had planned to travel to Christchurch so that he could lobby for Brisbane’s 1982 bid for the Commonwealth Games, but on Australia Day he returned to Brisbane after the flood crisis escalated. Vice Mayor Brian Walsh continued on the journey to New Zealand.

While most of page one of the Courier Mail on 31 January 1974 displayed a ravaged Jindalee supermarket and the death toll, it was with a sense of irony that they reported the lobbying event put on by Brisbane City Council to launch their attempt to host the 1982 Commonwealth Games. ‘Brisbane said it with wine, beer, chicken and strawberries’, the paper reported. Entertaining over 200 guests, including a prince from Swaziland and high-ranking games officials, the garden party cost in excess of $1000. Walsh told the gathering that Brisbane had the capital and skill to build the best sports stadium in the southern hemisphere for the Games, which would be held in October ‘when it never rains’.

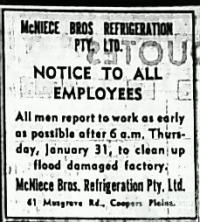

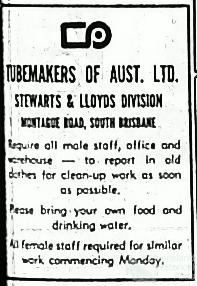

‘Many people not eligible for relief’

As milk was once again stocked in supermarkets and as radio and newspapers lobbied volunteers to turn out in force to clean up the flooded areas, the extent of the damage became apparent. The damages bill to Brisbane was over $200 million. In Ipswich four flooded West Moreton coal mines were closed permanently. In Milton, Jacaranda Press lost one-and-a-half million books and at the Castlemaine Perkins Brewery over one million bottles of beer were destroyed from the damage (the latter, of course, got prime coverage on the front page of papers). For householders suffering losses from the flood, the State Disaster Relief Plan administered a package of up to $3000 for victims. However, this was means tested, so someone earning over $140 per week or had more than $1000 dollars in the bank was not eligible. Even with the means tests in place, people queued for hours at disaster relief centres in an attempt to secure financial assistance.

‘This was the rampaging river’

From the first airlifts out of effected areas to the images of Oxley Creek flooding across the Rocklea area, aerial images dramatized the 1974 Brisbane Flood. Brisbane company Mapmakers sent up a plane twenty-nine hours after the floods peaked and some of their images looking from Jindalee to the city were published in the Courier Mail. The images were available to Government departments and the public, for a small fee.

As thousands of Queenslanders turned out to help in the clean up, some of them saw surveyors pegging out the extent of the flood. By mapping the flood the State Government claimed, on 31 January, that they could ‘safeguard in future development works’ as the records would ‘reveal areas of risk when defining future works and the volume of water likely to be encountered in future floods.’ The flood maps were significant future warnings, especially considering what Labor opposition leader Jack Houston said to State Parliament when debates were held over the floods on 5 March 1974:

[S]ome of the warnings that were given to the people about flood levels were inaccurate. Certainly they were not related to people’s homes. One of the unfortunate situations that developed during this time was that radio stations and the news media generally were giving flood levels at the Port Office. Account was not taken of the fact that the average person would not understand exactly what was meant by the river height at the Port Office. Certainly the media reported that floodwaters were coming down; but the fact is that a river height registered at the Port Office at a certain time will be reached earlier upstream and later downstream.

Houston experienced the downstream effect of this misinformation when people moved back to their homes as flood waters were still rising. The surveys resulted in the production of the 1975 Brisbane flood maps. What Houston did not note was that similar maps to inform the public were produced in 1893, 1933 and 1971.

Even with dramatic aerial images and accurate maps showing the extent of the flood, over the next three and a half decades it seemed easy to forget that Brisbane, built around its winding river, floods. One major development made complacency a little easier.

‘Flood threat past: Sir Joh’

On 18 October 1985 seven hundred guests gathered to listen to the Queensland Premier, Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen, open the Wivenhoe Dam. The following day the Courier Mail detailed the opening with a headline snatched from the Premier’s speech, ‘Flood threat past: Sir Joh’. The article reported, ‘The Wivenhoe Dam would act as a buffer against floods, the Premier, Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen, said yesterday.’ The dam cost $460 million and was located 70 km north-west of Brisbane, below the junction of the Stanley and Upper Brisbane Rivers, not far below the Somerset Dam. The Courier Mail reported, ‘He [Bjelke-Petersen] said he doubted if the 1974 flood could occur again because the dam would absorb an enormous quantity of water before any had to [be] released.’

‘Geological reconnaissance’ of the site for Wivenhoe Dam occurred in 1967 with construction approved by government in 1971. The dam was approved for both water storage and flood mitigation for Brisbane. Coming out of the dry period in 1970-71, Brisbane received minor flooding in February and April 1972 from two cyclones. Soon after this flooding a map of the proposed Wivenhoe Dam appeared in the Sunday Mail on 25 June 1972. At this time Queensland State Government also had consulting engineers study creek flooding and propose flood mitigation techniques. Overseeing the engineers was an interdepartmental committee made up of various representatives. One of the recommendations was the Wivenhoe Dam as a multi-purpose supply-mitigation project. In 1973 the acquisition of over 350 properties in the dam catchment commenced. After the 1974 flood the Wivenhoe Dam became a major project with wide support of politicians who wanted to give the appearance of taking action.

The article on Wivenhoe’s opening in papers on 19 October 1985, although in bold type, was relegated to page eighteen. The opening of the dam was not reported in other national papers. Two episodes in the lead up to the opening overshadowed it. First, the Queensland State Government wanted to spend $47,000 dollars on the opening with a lavish luncheon, but the Brisbane and Area Water Board (who would be responsible for the dam) and Brisbane City Councillors opposed such an extravagant waste of money, so the 700 guests were left eating jam pikelets. Following this, on the day before the opening a scuffle broke out in Queensland Parliament when Premier Bjelke-Petersen elbowed Liberal member for Stafford, Terrance Gygar, out of his way. A story of the Premier moving whoever he wanted out of his way was much more news worthy than a huge dam that could potentially hold back three times the water held in Sydney Harbour.

The Queensland Government, committed to ‘continuing development’, promoted their new dam with a double-page spread in the easy reading 20 October 1985 edition of the Sunday Mail. The Premier promoted the dam with his own editorial on its significance to Queensland. He wrote: ‘The opening of the dam is a fitting climax to 20 years of careful planning and construction from which many thousands of Queenslanders will derive immense benefits of water supply, power generation, flood mitigation and recreation.’ The image of the Premier accompanying the article showed him smiling and excited: happy to see yet another major project come to fruition. The Premier wrote, ‘An important feature of the dam is that it will reduce flood peaks and provide greatly increased protection against a repetition of the 1974 flood that devastated Brisbane and its surrounds.’ He concluded that the dam shows the Government’s commitment to build a ‘stronger state’ and a ‘better life for all Queenslanders’.

The double-page spread in the Sunday Mail captured a symbolic moment for Queensland. The new dam was discussed as both ‘An attraction for tourists’ and ‘Big by any standards’. The articles were accompanied by a half-page advertisement by Thiess Contractors advertising their pride at completing the dam, ‘it heralds new growth in Queensland.’ There were other advertisements by NewSteel who built the steel bifurcates and by construction contractors John Holland Group. Even Knots furniture who supplied the lounges to the Wivenhoe Administration Centre advertised their new furniture range in ‘Waterwash Colours’. The final advertisement was by the Queensland Government. Taking up half a page, the main image showed the dam’s spillway; inset on this was a map of the dam, another image of the Premier and images of the recreation facilities. A small caption told readers, ‘1974 is still a haunting memory for Brisbane. The new Wivenhoe Dam with more than half its capacity used for flood storage, will provide significant protection against flooding by lowering flood peaks.’ By promoting the dam for leisure and bringing people close to its enormous artificial-size the government and news reports softened people’s perception of the flood risk.

Even before the dam was completed, in February and March 1982, just like the events half a century before at Somerset, moderate flooding in the Stanley and Upper Brisbane Rivers was held back by Wivenhoe. A decade after its opening, in the first week of May 1996, over 600 mm fell in the Brisbane River catchment which saw many rivers rise to minor flood levels. Somerset dam filled from half to full and Wivenhoe filled from half to almost full. Both dams held back the water; again people in Brisbane did not experience a minor flood in the river. After a moderate event in 1999 the flood gates were finally opened with releases from Wivenhoe. Another decade passed, until on 12 October 2010, 100 mm fell in 48 hours, filling the dam and resulting in major releases of water.

Four months later Brisbane flooded. ‘“Without doubt the Wivenhoe dam has already saved Brisbane from a catastrophic flood,”’ the Queensland Premier Anna Bligh, at the height of a dramatic summer, declared to reporters on 11 January 2011. On the same day the Australian newspaper carried the headline, ‘Dams saves Brisbane, for now’. For now.

‘Worse than 1974’

The front page of the Courier Mail on 12 January 2011 warned, in both the alarmist headline ‘Worse than 1974’ and a full page satellite image of the Brisbane River on its ‘trail of disaster’, that ‘the flood will swallow Brisbane’. The day before the floods were due to peak in Brisbane’s worst flood in over three decades newspapers looked back to 1974 to draw a picture. History palliated the minds of Queenslanders.

Thinking back flood-prone Brisbane residents wandered over the landscape of memory to that year: how high did the flood get in 1974? Did it get to the top step on the verandah, or through the front gate, or to the first level of the apartment block? As Matthew Condon reported for the Courier Mail, ‘Memories come spilling back’. ‘At the back of the subconscious of every Brisbane citizen born before the mid-1960s, or thereabouts, there is a faint line, a watermark. Next to it is scratched a single year: 1974.’ His article probed the memory of Queenslanders and gave many of the blow-ins from the south a sense of local history.

But the floods were also a time for solidarity and community building, as an article on the following pages told: ‘Just as the Australia Day floods of 1974 defined the character of Brisbane of the late 20th century, the floods of this year will help define the character of 21st century Brisbane.’

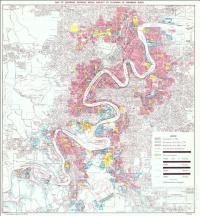

The previous flood could not be let go, almost every article referred to 1974. The opening article reported that ‘Up to 20,000 residents are set to be forced from their homes as the Brisbane River peaks tonight, unleashing more extensive flooding on the city than in 1974. That event remains one of the most significant in the city's history.’ The pages of the newspaper also carried maps, such as ‘The Water Path,’ showing where Brisbane was set to flood. Unlike the papers in 1974, aerial mapping had come a long way and the potential flood could be readily caricatured to inform residents of the effected flood areas.

As well as better aerial mapping technology, some necessary details were communicated more effectively in 2011. ‘Reading Rivers’ was an article that explained how the river height was measured. ‘All references to Bremer and Brisbane river heights use the Brisbane City Gauge reference point at the bottom of Edward St in Brisbane's CBD … the datum reference was about mean sea level, so last night's predicted city river level of 3m was about 3m above sea level. The Brisbane City river levels might reach 4.5m this afternoon and exceed the 1974 flood level of 5.45m tomorrow.’ Almost responding to politician Jack Houston’s comments in the wake of the 1974 flood, aerial mapping combined with reference to the city gauge provided residents with, at least, a preliminary understanding of what was coming.

In Brisbane, 2011 was a different flood to 1974 because suburban creeks experienced less of the downpour and water largely came from areas in the upper catchment. In twenty-four hours to 10 January the ‘Situation reports’ by SEQ Water showed that up to 300 mm fell in the already saturated Upper Brisbane and Stanley Rivers, and with continued heavy rain this caused major releases to protect the dam. And as the same reports noted, this was combined with major inflows from Lockyer Creek and the Bremer River into the Brisbane River. In the article, ‘Thousands set to flee as deluge day nears’ on page six, the comments of Brisbane Lord Mayor Campbell Newman were reported: ‘That's the key difference. We haven't, thankfully, had that suburban creek flooding problem. This time it will flood from the river back up the creeks.’ But looking across the State there were similarities to 1974.

Accompanying one article the paper provided a table, ‘The great deluge of 1974’, full of necessary facts from the previous flood. The first fact: ‘By late January 1974, almost every river in Queensland was in flood’. In 2011 much of the State was in flood. The newspaper reported that, ‘The floods that ravaged Queensland are saving one of their most devastating bursts for Brisbane … An unprecedented 80 per cent of the state is now a disaster zone.’ The 2011 Brisbane floods were building up to a dramatic conclusion from a disaster filled summer. Since the beginning of January the front page of the Courier Mail had carried images of flooded areas across the state.

‘Big wet set to get wetter’

Much earlier than 12 January 2011, Queensland had experienced major flooding across the entire State. The Courier Mail from the 1-2 January 2011 showed a cover image of Rockhampton locals having a beer in a dinghy out the front of the Fitzroy Hotel. There were more than 200,000 people and more than 10,700 properties affected in the Christmas-New Year floods across Queensland, an area approximately the size of France and Germany combined. The cost of repairs was estimated at $5 billion and both the federal and State governments offered assistance. Page nine of the paper showed a colour satellite image of the entire state with rainfall data showing above-average falls – Brisbane had 350 mm above average – and as the headline suggested, the ‘Big wet set to get wetter’.

On 7 January newspapers reported that ‘Queensland has become a sea of despair’. The ‘army chief’, Major General Mick Slater, was employed to co-ordinate the battle against the flood and clean up the mess in Queensland. Each day throughout January a map gave the ‘Crisis update’ showing the effected areas across the entire state. In response to the floods the federal opposition leader Tony Abbott proposed a series of dams across Queensland to mitigate against floods: the Australian reported this with the headline ‘Dam them’. The clean-up continued in Rockhampton.

On 10 January the Courier Mail showed music celebrities on the front page smiling and happy as ‘Australia unites’ to raise $11m for flood relief victims in a ‘deluge of donations’. A disastrous start to the year appeared to be turning back around.

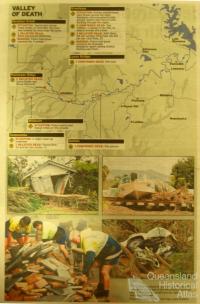

‘Swept away: 4 dead up to 50 missing’

On 10 January 2011, the Toowoomba airport received 180 mm in forty-eight hours, 60 of which fell between 1-2pm. Page one of the Courier Mail reported, ‘At least four people are confirmed dead, including two children, and up to 50 are missing after a massive wall of water carved a trail of devastation through Toowoomba and into the Lockyer Valley yesterday.’ The Queensland Premier Anna Bligh called the disaster the ‘darkest hour of the last fortnight’. She went on ‘Mother Nature has unleashed something shocking out of the Toowoomba region’. As newspapers across Australia reported on 11 January, the ‘tsunami’ went on ‘a trail of destruction’ through Toowoomba and left an ‘Armageddon-like scene’ in its wake.

The dramatic events of 10 January shocked Australia. But the water still needed to find its way to the sea. With such devastating events, and death tolls reported as high as 40, the anticipated flood to hit Brisbane potentially appeared to be ‘Worse than 1974’.

‘City of the Damned’

On 13 January 2011 the cover image of the Courier Mail showed the ‘River city’: inundated suburbs of Yeronga and Fairfield in the foreground looking across the Green Bridge with the river snaking its way around South Brisbane and past the city in the distance. Opening the paper the devastation appeared.

Brisbane wakes today to the might of the flood of 2011 – an event that will be [sic] forever loom large in the city’s history … With the untamed Brisbane River expected to have peaked at 5.2m before dawn, today up to 36,000 properties have been swamped. This peak laps at the historic 1974 level of 5.5m, the disastrous event authorities believed could never be repeated.

In the following pages the Toowoomba and Grantham tragedies were reported upon in detail. These included the ‘Valley of death’ a map of the Brisbane River catchment and the places – Murphys Creek, Grantham, Postmans Ridge, Withcott, Toowoomba and Gatton – that had been devastated by a ‘wall of water’. Comparing this map to the other maps that were produced in floods in 1974, and even 1953, the shocking title shows a heightened fear in the community in 2011 and how people’s perception of the landscape was heavily influenced by events in the upper catchment, and a realisation that Wivenhoe Dam might not ‘save’ Brisbane.

The national dailies reported the flood in headlines that were much more dramatic and shocking. On 13 January 2011 Sydney’s Daily Telegraph described Brisbane as the ‘City of the damned’. Reporting, ‘Walls of water swamp Brisbane: All Brisbane can do is wait to see how devastating today’s flood peak will be. Whole suburbs are expected to be lost when the city’s river peaks this morning.’ The Australian told readers ‘Floodwaters show no mercy’, followed by ‘the heartache that has gutted the country arrives in the capital.’

With such drama, and the flood waters only just arriving at their peak it did not take long for reporter Headley Thomas to start pointing the finger in his search for answers and a scoop. ‘The comprehensive 1999 Brisbane River Flood Study made alarming findings about predicted devastation to tens of thousands of flood-prone properties, which were given the green light for residential development since the 1974 flood.’ In the following days the operation of Wivenhoe Dam would also come under attack by reporters. Next to Thomas’ article was a predicted flood inundation map (a much more detailed map than appeared in the Courier Mail on the same day) which also showed the Brisbane suburbs already in flood and the number of properties already affected – one of the suburbs on the map was Jindalee with 484 flooded properties.

In 2011, flood waters reached a height of 4.46m at the city gauge in the early hours of the morning on 13 January. The following day Brisbane had become, ‘The drowned city’, as the Sydney Morning Herald showed its readers.

As the flood receded the Courier Mail told of ‘Defiance: as the flood of 2011 recedes, the fightback begins’. The clean up gathered momentum and by 17 January Brisbane began to appear as a ‘Field of broken dreams’ when rubbish dumps began to crop up in city parks and green-spaces to hold discarded possessions ruined by the flood. To help, the federal government offered, without means test, an initial $1000 in assistance to affected Queenslanders.

‘A 35-year warning of Brisbane flood ignored’

Reporters told people they needed answers and bombarded them with a tide of stories focusing hindsight and blame on property development and dam operation. ‘History forgotten in rush to riverfront luxury’ on the front page of the Australian juxtaposed the 2011 and 1974 floods. It showed the same landscape separated by three decades of development: a flooded luxury apartment in Tennyson that had been built just two years ago next to the flooded Tennyson Powerhouse in 1974. How could the developer, the Brisbane City Council or the State Government allow the building if the area was known to flood?

Questions over development were warranted, but were exactly the same questions that occurred in 1974 when places such as Jindalee were flooded. In 2011, however, many places were known to flood and revoking the explosion in development along Brisbane River seemed impossible, even to reporters.

So the tide of blame shifted to the operation of the Wivenhoe Dam. At the time of the dam’s construction it was perceived as removing the ‘flood threat’ but in 2011 it was claimed to have both increased flooding or not been adequately emptied before the wet season. Much of the blame pointed to the dam’s operation manual. A document that was constructed by legislators and water engineers – people, like the same ones who construct dams – providing a list of instructions about how best to hold back water in a flooding river.

Wivenhoe Dam was filled with ambiguity from the start. The Bureau of Meteorology report after the 1974 floods provides a poignant example. The Bureau suggested:

In situations where the major flood contribution occurs in catchments below Somerset Dam and the proposed Wivenhoe Dam, there are considerable problems in deciding when to empty the flood storage. If floodwaters were retained by the dam for too long not only would there be major and prolonged flooding upstream from the storage but the dam would become virtually useless for flood mitigation downstream in the event of a repetition of excessive rainfall. Meteorologically such a situation has already occurred (in 1893 when there were three floods within a month) and a recurrence appears inevitable.

But then a few pages later they suggested: ‘Therefore it seems certain that unless major flood mitigation schemes, such as the proposed Wivenhoe Dam, are implemented, floods even greater than those of 1974 will again be experienced in Brisbane.’ On the one hand a major dam can only do so much and needs to be managed properly but on the other hand a dam is needed to protect Brisbane.

Depending on climactic cycles, such ambiguities continue to circle in the media’s coverage of the dam in either flood or drought. For example, in 2006 at the height of the drought the Courier Mail published a feature article, titled ‘High and dry’ by Mathew Condon proclaiming the lack of foresight by the government in securing new water resources after Wivenhoe was built. An empty Wivenhoe Dam was the point of contention as Brisbane was set to run out of potable water. But as the floods hit, Wivenhoe was once again in the media as its ability to protect Brisbane came under attack. This was reported in the Courier Mail, but most heavily in the Australian with articles such as ‘Engineer bores a hole in dam untruths’ 19-20 March 2011 by Headley Thomas. In either drought or flood it seems that Wivenhoe is damned.

People forgot that Brisbane floods. On 12-13 February 2011 the headline, ‘A 35-year warning of Brisbane flood ignored’, appeared in the Australian newspaper signposting an article by Hugh Lunn – venerable journalist who won a Walkley award for his coverage of the 1974 floods. Through his investigations as a journalist on the Courier Mail, as early as 1972 Lunn was warned about the flood risk in Brisbane.

The warning came from A.J. Shields, the head of the Bureau of Meteorology in Brisbane who didn’t mince his words (the same man that compiled the Bureau report after the 1974 floods). Showing graphic images from 1893 and 1974 Lunn’s article carried a sense of history. It quoted Shields in the 29 January 1974 edition of the Australian as saying: ‘from a hydrologist’s point of view a lot of Brisbane people have built homes in the river and the creeks rather than on them … the Somerset Dam above Brisbane had created misplaced confidence.’ And with his sense of the 1974 floods, Lunn commented on the 2011 episode and the problems of development, ‘since then, Brisbane has been rebadged the River City and citizens have been urged to “embrace the river”. And we did too, with two walking bridges, a cycle bridge, a green bridge, a railway bridge, plus traffic bridges.’ And so the current flood had shown that not only had people embraced the river but ‘the river had embraced Brisbane.’

Environment and history

As the headlines which appear as subheadings throughout the article suggest one of the ways the print media maps floods is by creating stories. We can read these reports with pessimism and observe the media recycling the same narratives in different flood events. At times saying ‘I told you so’ about warnings that were never heeded and at others positing blame on developers, planning legislators and the operation of dams. But looking collectively at the media, and their stories, we see that they might be onto something. We continue to tell the same stories because, quite simply, floods are a natural cycle in the Brisbane River. In other words, a sense of history, which was especially evident in the 2011 episode, is also a sense of the environmental cycles that recur in the places we dwell.

The print media’s mapping of the Brisbane floods in 1974 and 2011 show both recurrent and different themes. Technological developments with up to date internet coverage and accurate mapping played an important role in how the floods were covered. But it was the dramatic events of 11 January 2011 in Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley that resulted in heightened fear in the community. This fear was exacerbated by the media and marked a critical difference to the previous major flood. As waters flowed down to Brisbane it appeared that 2011 would be worse for Brisbane than 1974. After both floods, particularly in Brisbane, urban development in flood-prone areas was heavily criticised. After 1974 it seems many of the lessons were not heeded and development grew apace. In 2011, however, this theme was quickly let go as many flood-prone areas could not be cheaply repossessed as was possible in 1974, when remarkably very little land was repossessed. Most reporters quickly turned to the Wivenhoe Dam as a source for stories and blame and intrigue.

Having an ongoing perception of our landscapes is most at task in the wake of the 2010-11 episodes of disaster across Queensland. Knowing tomorrow, in five years, in ten years, in the period before the next major flood, that the Brisbane River is a highly mobile environment prone to major flooding is critical in how we know and relate to our landscapes.

References and Further reading (Note):

H.P. Somerst, ‘The 1893 Flood: Recollections by Mr H.P. Somerset’, ms F540, St Lucia, Fryer Library

References and Further reading (Note):

Bureau of Meteorology, The big wet – January 1974, Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology, 2011

References and Further reading (Note):

Brisbane Floods 1974, Brisbane, Channel 7, 1974

References and Further reading (Note):

Queensland Parliamentary Papers, Brisbane, Government Printer, 1974, 2633-2634

References and Further reading (Note):

K.R. Warner, ‘Brisbane River damsite – geological reconnaissance’, Record 1967/8, Brisbane, Geological Survey of Queensland, January 1967

References and Further reading (Note):

Report on proposed dam on the Brisbane River at Middle Creek or alternatively Wivenhoe and flood mitigation for Brisbane and Ipswich, vol. 1, Brisbane, Queensland Co-Ordinator General’s Department, June 1971

References and Further reading (Note):

Director of Meteorology (BOM), Brisbane Floods: January 1974, Canberra, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1974

References and Further reading (Note):

Bureau of Meteorology, Known floods in the Brisbane & Bremer River Basin, Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology, 2011,

References and Further reading (Note):

SEQ Water, ‘Appendix E: Situation Reports’, Report on the operation of Somerset Dam and Wivenhoe Dam, Brisbane, Department of Environment and Resource Management, 2 March 2011, www.derm.qld.gov.au/commission/documents/appendix-2.pdf

Keywords:

1893 flood, 1974 flood, 2011 flood, Brisbane River, floods, media, newspapers, Somerset Dam, Wivenhoe Dam