- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

Luke Keogh

By:

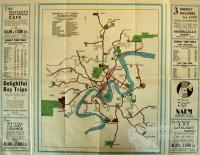

Peter Spearritt Brisbane trams commenced operation in August 1885 by the Metropolitan Investment Company with horse drawn cars on a fixed track. A decade later a new company formed, the Electric Tramways Company Limited, and they took over the electric parts of the tramways, including the line from Logan Road to the southern end of Victoria Bridge which began in 1887. On 21 June 1887 electric cars commenced and within a year the horse drawn system became redundant.

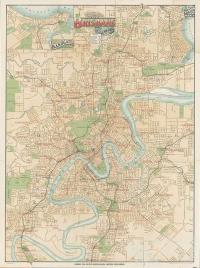

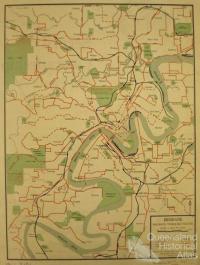

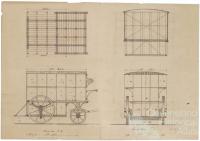

The narrow streets in Brisbane, especially in the inner city, meant limiting the body width of vehicles. As in many other Australian cities, municipal authorities were attracted to the idea of owning and running tramways, not least as the trams could be powered by government-owned electricity stations, powered by coal. In January 1923 the Brisbane Tramways Trust acquired the private company and by December 1925 the tramways were under the control of the Brisbane City Council, which constructed a large electricity powerhouse at New Farm. The track expanded until 1962 providing a maximum route length of 106 kilometres.

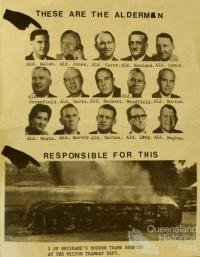

Fire

Fire destroyed the Paddington tram depot on Friday 28 September 1962. Sixty-five trams were lost from the 366 strong fleet. Although a major disruption, this disastrous event had the effect of crippling Brisbane’s tram network at a time when politicians and planners were intent on laying more bitumen for motorists and buses.

The plans for the new meal room in the Paddington tram depot located on La Trobe Terrace had taken all of July to get right. Details mattered: things like the power points and the lights were important considerations. At the end of one plan, dated 10 July 1962, the concluding comment by the draftsperson over whether a new locker was needed in the carbuilders and electricians workshop said, ‘bearing in mind that this would be a good time to clean out’. On 30 July 1962 the final plan was complete. On 14 August the purchase order of £104 was signed by the department of transport and the new lighting was ready to be installed at the Paddington depot. In late September, a little over a month later, fire destroyed the Paddington tram depot, including sixty-five valuable trams.

By Monday morning 1 October 1962, three days after the fire, the department of transport handled peak loading with only minor delays on one or two routes. Fifteen buses from the New South Wales Department of Transport left Sydney on the Sunday and were in service by the Wednesday. Without Paddington depots the city became crowded and many north-side trams had to be housed at the Ipswich Road depot. The fashionable diesel buses became even more economical considering the increased mileage of running northside trams to Ipswich Road. When the city council received their £80,000 insurance cheque after the fire they spent it on thirteen new buses, operational by June 1963.

Discussing the heavy losses after the Paddington fire the Department of Transport’s annual report for 1962-63 noted:

In an endeavour to reduce these additional costs, action was taken to substitute buses for trams on the following routes: ̵ Rainworth, Toowong, Kalinga, Bulimba Ferry – the substitution was implemented on 25th December 1962.

The location of the depot determined the location of the routes to be substituted. By the end of 1962 the total route track length contracted to 97 kilometres. It would continue to contract until the end of the decade with the gradual closure of other lines. Brisbane residents were shocked. Protest committees were organised in Toowong and Kalinga.

Protest

‘The City Council as an institution and the rate-payers and citizens have been treated with contempt by the Lord Mayor and other members of the council committee’, reported the Courier Mail on 22 December 1962 after the announcement of the removal of tram services on the north-side. On 24 July 1963, Kalinga and Toowong residents summoned the Lord Mayor Clem Jones to a deputation on the removal of trams in their localities. Reverend C.H. Nicholls, representing the people of Toowong, explained in a letter to the Mayor that the loss of trams was an issue of ‘TERRAIN and HARDSHIP’. Nicholls would go on to argue that, ‘The people are very perturbed at Toowong. Because of this we feel it is a ruthless upsetting of life – it is not just a matter of transport to and from work – but all living pattern’.

By the end of 1963 Toowong and Kalinga residents were still protesting, and on 12 December over 500 residents met to protest the Brisbane City Council’s removal of trams. They wanted their transport pathway back. They had already sent a petition to Council signed by over 700 residents, they demanded a deputation with the Lord Mayor and they had been screaming to the powers that be since the closures the previous year. The council was not at the meeting to negotiate – the northern lines were to be closed.

The Kalinga protest committee wrote to the Lord Mayor informing him of the protest meeting held with 500 residents wanting trams back. They wanted a meeting because of the unsatisfactory bus services. Impolitely the letter ended demanding a response within fourteen days.

The Council had continuously stalled protesting residents. Reading the Department of Transport files it is with some surprise that, in the same handwriting which had been used on other letters from the Lord Mayor’s office, an instructive note was passed between members of the department and the Lord Mayor. On a simple square piece of paper was written, ‘wait until they write again’.

Five hundred residents met in Kalinga demanding their trams back and all the city council did was stall them into submission. Like being stuck in a traffic jam, Brisbane residents were left stifled and irate.

The Lord Mayor Clem Jones had already made it clear:

The future of public transport in Brisbane is completely tied up with some effort in next few years to deal with traffic movement. … If it had not been for the fire, there would have been no change in tram services anywhere’.

The Council decided to build a new bus depot at Toowong instead of rebuilding the Paddington depot and in doing so abandoned the tram lines in the northern areas.

Finally, on 18 March 1964 protestors got their deputation. From the outset the deputation was filled with theatre. At one stage while the Kalinga resident Miss Hartigan complained about the difficulty of getting on trams at the Kedron Hotel terminus, the Lord Mayor interrupted to pick up the telephone mid-meeting and call the Chief Clerk J.C. Slaughter to tell him to request the traffic commissioner to install pedestrian lights at the spot. The Lord Mayor made it clear that the trams were not coming back in Kalinga, but a network wide closure was not going to happen. Clem Jones’ final comment at the deputation: ‘No intention to remove trams. They will not be, as stated.’ The following day the headline in the Courier Mail read: ‘Council will not eradicate trams’.

Days are numbered

The changeover to buses on the inner north lines provoked questions related to Brisbane’s future transport needs. Throughout 1963 when protestors were organising themselves and demanding their trams back, internally the mayor, the chief clerk and the department of transport were quantifying the savings. The Paddington fire provided council with an opportunity to conduct a comparative study of the tram and bus in Brisbane.

The order came from the top. On 6 February 1963, less than two months after the conversion, the Lord Mayor sent the Chief Clerk a memo requesting information comparing trams and buses on the recently changed routes. In two months, there was a 13% decline in passenger numbers on comparable tram/bus routes. However, the Department of Transport informed the Lord Mayor that there was ‘no general decline in patronage’. At the time of the conversion, the council added a new bus route (not comparable to any tram route) that travelled along Lutwyche Road, so the department added the increased patronage on this service to the bus numbers to arrive at similar total. They also didn’t take into account dramatic declines in specific locations: in Kalinga and Bulimba there was a 47% and 29% decline respectively.

The following month the more comprehensive ‘Report on three months operation of tram to bus conversion’ was supplied to the Mayor in a memo on 28 March 1963. Total savings to the council was approximately £56,000, but had one-person operation been implemented it would have been as high as £81,000. But there was one other major cost not factored into this: the damage to roads caused by buses. The manager of the Department of Works estimated £54,000 and approximately another £40,000 over the following year.

Buses and trams were both very different systems, and each required a different vision – one long term and more expensive and the other short term and less expensive. The bus appealed to the economically rational, short term preoccupations of councilors and city engineers grappling with motorists’ resentment of growing traffic congestion. Their concerns were further validated by a major planning study released in 1965.

Transportation system

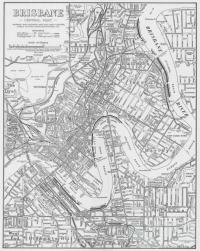

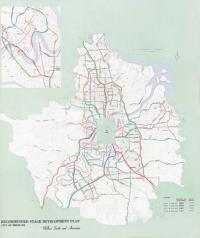

The rapid rise in the use of the private motor car was a major challenge for urban planners in cities around the world. Between 1949 and 1963 Brisbane motor car registrations rose from 80,800 to 298,800, a rise of nearly 270%. In the same period public transport decreased 32%, but the peak demand of the service remained at its height thus preventing a reduction in tram and bus services. The largest decline of public transport use was Sunday patronage which fell 48% in this period.

In the middle of 1963 the urban planner Wilbur Smith travelled from the United States to Brisbane. On 16 September 1963 he wrote a long letter to H.A. Lowe, the deputy commissioner and chief engineer in the Main Roads Department, following up his visit to Brisbane:

You are certainly correct in wanting to plan as soundly as possible, so that all expenditure will produce maximum benefits, and so that all forms of transportation will be integrated into a TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM aimed at meeting the long-range (20-30 years hence) needs of the rapidly expanding city.

Smith went on to make a list of key areas where data needed to be collected so that he could make recommendations to council. One of the points of data collection Smith requested was to ‘Compare the 1960 date with today’s traffic and travel volumes’. In short, extrapolate three years data twenty years into the future.

The Brisbane Transportation Study by Wilbur Smith and Associates released in 1965, and quickly accepted by Brisbane City Council, changed the face of Brisbane. The one-way double lane thoroughfares through the city and inner suburbs and the riverside expressway were recommended. Indeed, developments in Brisbane four decades later such as the Go-Between Bridge and a road following a similar course to the new Clem Jones Tunnel were detailed in the Wilbur Smith report. The movement of private vehicles dominated the study. As such public transport, as had already happened in most US cities, had to fit in with the new ‘Street and highway plan’, the most suitable to this model was the bus. The report summary recommended ‘Replacement of all trams and trolley buses with diesel units’. The removal of Brisbane trams from streets was a critical first step in creating new, prospectively high-speed arterial roads. Very little consideration was given to the impact of accidents on such roads, which could then be brought to a standstill. The report suggested that ‘immediate action’ should be taken to purchase buses and to phase trams out in three years.

The trams were replaced by 340 new Leyland Motor Company buses that cost Brisbane $6.8 million. The choice in 1967 not to include tram tracks on the Victoria Bridge, historically one of the great assets of the tram network, signaled the end of trams.

Destination Ascot

Car 534 ran the last tram trip from Balmoral to Ascot on 13 April 1969. When it arrived in the city it was met by car 554, the latter had a police escort and was carrying numerous politicians from Brisbane. Near the Treasury building in the city, trams were forced to stop as close to 300 youth became hostile and tried to tear apart their trams. Just before midnight car 534 passed into the Ipswich Road depot for the last time. It was met by a crowd of nostalgic people and police in case of trouble. Car 554 travelled to the Milton Workshops and Clem Jones moved the controller to the off position; the tram would be one of the first acquired by the Brisbane tramways museum.

The abandonment of trams in Brisbane was surprisingly late compared to many other Australian cities: Adelaide (except the Glenelg line) and Perth in 1958, Hobart in 1960 and Sydney in 1961. Throughout this period Melbourne shunned the almost worldwide trend for abolition, and committed to retaining its tramways.

The policy of the department of transport was to scrap tram cars but public protest over the already sensitive policy to remove trams caused council to rethink their policy on tram disposal. An article appeared in Queensland newspapers telling readers that Council was selling tram cars. Between 1968 and April 1970 the Council received hundreds of letters from residents in areas across the country, from Northern New South Wales to Chinchilla. Some trams were also acquired by schools to be turned into play equipment for children.

The letters of request are an elegy to the tram. Some people protested the tram removal while others just wanted to continue life on the permanent way with the tram as an artifact or abode. Some of the more interesting requests reveal the antiquarianism that trams evoke in so many people. Like antique dealer Garry Makin of Carnaby’s Antiques on Lutwyche Road, who wrote on 31 March 1969, ‘I want one mainly for decorative purposes and plan to have it painted like a carousal as a garden showpiece.’ A proposal from the Writers Guild of Queensland requested trams for lodges at their writers’ retreat which was ‘free from the distractions of city and suburban life.’

Many of these letters were addressed to the Lord Mayor Clem Jones, with people requesting trams from him personally. This displays both the singular style of Jones’ politics but also the view in the public that it was indeed Jones who brought about the removal of trams. One of the most dramatic letters to ‘Our Lord Mayor’ came from a desperate Mrs Hanahan on 14 March 1969, who did not have enough money to buy a tram and wanted to pay $5 per week to Jones directly so that she could install a tram at the rear of her daughter’s home in Wacol. She wrote ‘It would be the only home of my own that I will own.’ She concluded her letter with a note on Jones’ leadership, ‘The majority of Brisbane people admire you. You are an up and go man. Brisbane’s Face Change, will be a lasting monument to you for future generations. ‘Good Luck Clem’.’

Why did cities around the world get rid of their trams?

Tramway systems were ripped up in almost all cities in the English speaking word between the 1930s and the 1960s. The first major removals took place in the United States where the onset of mass car ownership saw motorists increasingly frustrated by the traffic jams exacerbated by trams, especially when they did not have their own right of way. Sometimes systems were purchased by motoring interests simply to close them down. London got rid of its trams by 1952, for similar reasons, but the key decision makers at the time never imagined that mass car ownership would come to Britain, or that replacing trams with buses, in often narrow streets, would not, in the long run, eliminate traffic jams. By the 1970s the largest remaining tramway systems in the world were in the Soviet block, including Russia.

The only large system left in the English speaking world was Melbourne, where a combination of a powerful bureaucrat who ran the independent tramways board, a polite motoring organization (the RACV, in marked contrast to the aggressive campaign run by the NRMA in Sydney to rid that city of its trams) , some magnificent rights of way (Victoria and St Kilda parades) and wider CBD streets saw the system survive. Melbourne now has the largest tramway system, by route length, in the world. St Petersburg’s system is somewhat smaller, but still carries more passengers.

Tram for the Gold Coast and Brisbane’s busway network

Many cities around the world have re-introduced trams over the last decade or so, including Sydney. When the Gold Coast, with the lowest proportion of public transport use of any large city in Australia, came to contemplate its options, the City Council opted to build a light rail system down the middle of the Gold Coast Highway. Opened in 2014, it capitalizes on the relatively high densities along the coastal trip, from residents to visiting tourists.

Brisbane’s greatest public transport achievement over the past twenty years, the busway system that hangs off freeway reservations, now carries more passengers (70 million per annum) than the city’s suburban railways (55 million). And at least the planners of the busway system had the wit to engineer it in such a way that it could, in future, take light rail rather than buses.

Many of Brisbane’s bus routes still follow the old tram lines, and some tramway shelters still survive on those routes. But the new busway system, which separates buses from other forms of motor transport, utilizes the extra land buffer at the side of freeway reservations, including the motorway to the Gold Coast. Regrettably, the privately funded tollways and tunnels that Brisbane saw in the early twenty-first century, have done very little for public transport usage. One of the tunnels, the ‘Clem 7,’ is named after the late Clem Jones. With only one third of the predicted motorists, it went broke, with shareholders losing billions of dollars. How much more sensible it would have been to invest that capital in a tunnel to be used for the city’s overtaxed railway system, where commuters from the southern suburbs and the Gold Coast have to put up with standing room only in the morning and evening peak hours.

References and Further reading (Note):

Brisbane City Council transport ephemera, ms117309, John Oxley Library

References and Further reading (Note):

Tram files, 1885-1971, Box 1 to 70, Brisbane City Archives

References and Further reading (Note):

Howard R. Clark and David R. Keenan, Brisbane tramways: the last decade, Transit Press, San Souci, 1977

References and Further reading (Note):

Wilbur Smith and Associates, Brisbane transportation study, 3 vols, Queensland Main Roads Department and Brisbane City Council, 1965

References and Further reading (Note):

Peter Spearritt, ‘Why Melbourne kept its trams’ 12th Australasian Urban and Planning History Conference, Wellington, 2014

References and Further reading (Note):

J. Richardson (ed), Destination Valley, Traction publications, Chadstone, 1956

References and Further reading (Note):

Wilbur Smith and Associates, The southeast Queensland-Brisbane region public transport study, Queensland Department of Transport, 1970

References and Further reading (Note):

Brisbane City Council, Brisbane city centre master plan 2006: a vision for the future of our city’s centre, Brisbane City Council, 2006

References and Further reading (Note):

Peter Spearritt, ‘Tramways’, The Australian Encyclopedia, Australian Geographical Society, Terry Hills, NSW, vol. 8, pp.2893-5

References and Further reading (Note):

Peter F. Moses, ‘Trams for Australian cities with particular reference to Brisbane’ MA. Thesis, Department of Regional and Town Planning, UQ, 1987

References and Further reading (Note):

Lionel Frost, ‘The history of American cities and suburbs: an outsider’s view’, Journal of urban history, 27, 3, 2011, pp. 362-376

Date created:

3 March 2015 Copyright © Luke Keogh and Peter Spearritt, 2015