- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

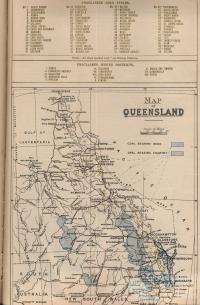

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

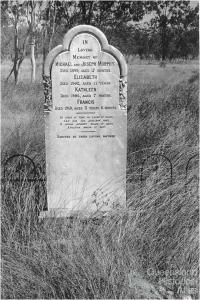

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

Jan Wegner Scattered across the tropical north of Queensland are hundreds of dead towns. Called into being by mining, they were abandoned when the minerals ran out or proved to be unprofitable. Some measured their lifespans in weeks or months; others survived for years, or lived on in a kind of half-life as the home of a fossicker or cattle station homestead. They can be found in rainforest, savannah and Spinifex country. They exist now as evocative names on old maps – Mungana, Calcifer, Goldsborough, Black Jack – with only ruins and fragments of corrugated iron, crockery and glass and perhaps a few graves to mark where people once lived, worked, loved and died.

Mining

Tropical Queensland is one of the world’s major mining regions. Mining has occurred south of the Tropic of Capricorn in this state, but the only important areas are the Gympie goldfield and Ipswich coalfields. In the north, copper, gold, tin, silver, lead, wolfram, bismuth, scheelite, zinc, coal, uranium and many other minerals have been exploited since gold was discovered in Clermont in 1861. Most were mined from the solid rock, needing expertise and money for equipment and treatment plants. However, gold, tin and wolfram could be washed from alluvial deposits in the creek beds or soil alongside; miners just needed rudimentary equipment, strength and energy. The hope of making a rich strike rapidly drew people into Queensland, following the prospectors as they fanned out from earlier discoveries. The thin mantle of settlement thrown across the colony by pastoralism was rapidly augmented. Roads, mail services, and towns were soon established to serve the new arrivals. They were encouraged by a colonial government anxious to settle Queensland’s big empty spaces. Mining certainly did this better than any other industry, bringing thousands to inland Queensland.

Towns

Mining, especially hard rock mining, created almost instant urbanisation. The miners, storekeepers, publicans, butchers and Government officers tended to cluster near any water supply within walking distance of the mines. At first they lived in tents or bark huts, but if the mines continued beyond the rush stage, more substantial buildings sprang up – even brick, such as in Thornborough. After the late 1880s most buildings would be corrugated iron on a timber frame. They were oven-hot on summer days but the iron sheets were easily packed for transport if the owner moved on. If the town grew, it acquired banks, specialist shops, a school, a hospital, churches, and halls. One settlement would usually become dominant, the administrative centre, ringed by smaller townships or camps serving clusters of mines. Within a ten kilometre radius of Croydon were Carron, Mountain Maid, Richmond, Jubilee Camp (Goldstone), Gorge Creek, Croydon King, Moonstone, The Springs (Flanagan’s), Table Top, Golden Valley, Homeward Bound, Mark Twain, Mulligan’s, Upper and Lower Twelve Mile, True Blue, and Golden Gate. As the mines failed, these satellites died, with only Croydon surviving as a local government centre and service town for surrounding cattle stations and travellers between Cairns and Normanton. This became a common story throughout the north.

Mining peaked in the period between 1870 and 1920. It declined because of world events such as World War I driving up the cost of mining supplies, and the Great Depression driving down the price of minerals. During World War II the north became a battlefront, and short supplies meant that only large efficient producers such as Mount Isa were allowed to operate. Pastoralism re-emerged as the major industry inland and it was unable to support the same level of population as mining. The North was a much quieter place in the 1950s and 1960s. Unless towns could find another industry to support them, they went back to the bush.

Abandoned mining towns

What might a visitor expect to find in an abandoned mining town? Resourceful inhabitants scavenged failed mines and mills, so bricks from smelters, pieces of mining and milling equipment and lengths of tramway might appear. Clusters of tins, bottle glass and broken china back onto house sites; no garbage collection services in these settlements. Venerable mango, tamarind and frangipani trees might survive, or a spiky sisal plant. Short house stumps, perhaps with a stump cap attached, and lengths of guttering might be accompanied by the twists of wire used to tie corrugated iron onto timber frames. Tangled lengths of fencing show where pig, goat and fowl yards stood, or where an embattled householder defended a home and garden against the hordes of goats. Small treasures, like a slate pencil, a rusty roller-skate, or a mineral specimen in a former schoolyard tell much about the people who lived there. Somewhere nearby will be a cemetery, often dominated by the graves of children. How did families feel when they had to leave these small graves behind?

Mungana

Sitting among spectacular limestone bluffs, Mungana was the railhead for the Chillagoe Railway. It began life in 1896 as a mining camp for the Girofla and Lady Jane mines, the largest on the Chillagoe field. When the railway came in 1901 to tap the lead and copper ore for the Chillagoe smelters 11 km away, the town moved a kilometre north to the railway station. Life was rough in a mining and railway town but soon settled down with a school, churches, hall, police station, hospital, library, post office, market gardens, rifle range, racecourse, butcher, baker, draper, café, general store, and five hotels. The fortunes of the town followed those of the mines; it declined when they were closed in 1914 after the mining company went bankrupt, but revived when they were re-opened under State Government ownership in 1919. It was later alleged that two Government ministers owned shares in the mines before the purchase; the ‘Mungana Scandal’ made the town a household name. The big mines closed for good in 1926, but though the town declined once more, it lingered for some time as the railhead for a large pastoral and mining area. The end of regular train services in 1958 killed it off and by 1965, it was abandoned. It is now the State’s first heritage-listed Archaeological Area.