- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

Sean Ulm

By:

Susan O'Brien

By:

David Trigger

By:

Michael Williams ‘Places’ are central to the ways in which people construct their understandings of the world. A ‘sense of place’ is rooted in feelings of belonging, attachment, connection and ownership, interlinked with memories, experiences, emotions, histories and identities.

The idea of ‘place’ itself is elusive, being variously thought of as a named location, site of local activity, foundation for social and cultural knowledge and meaning, or as a particularly memorable sensory experience. Places can be transformed over time according to broad cultural dispositions as well as economic and political drivers. Places, then, are multidimensional, with discrete localities, landscapes and sensescapes overlapping in our constructions of locations. A ‘sense of place’ is particularistic; it is both a personal and collective social construction framed through engagement with a particular place, its landscape and material properties, both tangible (eg buildings) or intangible (eg natural features of environment). However, while places are always experienced locally, those constructions are embedded in our worldviews; that is, how we perceive and engage with new places and landscapes is informed by our previous encounters in other places and times.

The bonds individuals or social groups form and maintain with places is a vital source of individual and cultural identity, and a point from which people orient themselves to the world. People use story, dance, song and art to talk about the places that matter to them, and the ways in which their lives and identities are influenced, in both positive and negative ways by place. People could hardly live without telling stories, both to themselves and to others. These stories are not simple acts of description, but the ways in which people make sense of the world, the details of their daily lives, their relationship to others, and their family histories. Stories become embedded in people’s memories and in their family and community stories, and in the act of telling and re-telling stories individuals situate themselves in vast and intricate cultural landscapes. The stories we tell are what makes any place become ‘our place’ and where some authority, ownership, belonging or, at least, connection to the place can be expressed and maintained. Sharing stories with friends and strangers alike, provides people with feedback that helps to reinforce, validate and affirm the connection people have with place.

While some people consider place to be mostly a background component of their everyday lives, others pay close attention to the character of the places in which they live, encountering and engaging with features of the natural and built environment. A place is more than just the stage setting for human action, and is itself socially created and creating. In remembering, residing at, visiting or moving through places, people undergo complex experiences, feelings and behaviours. These can include a sense of history and family connections, a moral foundation for a sense of personal identity, feelings of coherence, stability, attachment and ownership. Places can also produce a sense of instability and disconnection in some circumstances, particularly through unfamiliarity or memories of negative experiences or events.

By listening closely and working closely with Aboriginal Australian people, for example, James can ‘hear the composed ontology of place’ in the way in which ‘place’ is performed by storytelling, singing and dancing, transforming the singers and dancers into the ancestral creators of those living places. Contemporary Aboriginal understandings of landscape are informed by such broader narrative traditions that articulate particular or general features of the natural and cultural world with specific mythological and historical figures or events. Through such 'performance' of place, the feelings, beliefs and experiences that relate to locations and landscapes are intricately embedded in people's collective memories.

The socially constructed nature of places means that they are mutable, changing with the nature of engagement. When people are displaced, whether physically or psychologically, their relationships with places change. In Queensland the nature of engagement with place was dramatically impacted by the encroachment and establishment of European occupation on Aboriginal traditional countries. In the nineteenth century, introduced diseases and frontier violence caused major reductions in Aboriginal populations throughout Australia. From around 1850 onwards Europeans made increasing inroads beyond the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement, with the declaration of pastoral districts throughout the state. The settlement was broken up in 1840 and declared open for free settlement in 1842 but by this time squatters were already at the 50 mile settlement limit. However, large areas remained unused by Europeans in the early period of settlement and Aboriginal people continued to live in their traditional lands. By the late nineteenth century the spaces on the map were filling in with Europeans; Aboriginal populations coalesced into fringe camps at townships or attached themselves to cattle stations established on traditional lands. In the early twentieth century Aboriginal people were at times forcibly removed to reserves and missions throughout the state under the provisions of the Aboriginal Protection and Restriction on the Sale of Opium Act 1897.

Until the 1950s the movement of most Aboriginal people was tightly controlled in Queensland, limiting opportunities to visit places. Some of these areas remain unavailable to this day owing to access restrictions to freehold land. However, often enough knowledge transmission about place does not cease when Aboriginal people are displaced from their country. As many Native Title and land claim cases illustrate, Aboriginal people even when physically removed from their traditional countries continue to 'possess' their local places and landscapes, imprinting them with their life stories, histories, memories and experiences. The performative nature of connections to place has continued to occur through recalling memories and feelings and telling stories about those places. Thus, for many Aboriginal people, knowledge about and also connections between places highlight the continuity of social and spiritual relationship with land, place and culture and the importance this plays in creating, expressing and maintaining contemporary personal and social identities.

Different people and different social groups read, value and relate to places differently. Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians draw on different narratives to situate their experiences with place in time and space. When these different gazes are applied to the same location there can be a conflict of perspectives. However, places can provide a common setting to explore the shared nature of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal history in Australia. Such shared history in places plays a key role in the way in which people situate themselves in the vast and intricate landscape of both Aboriginal and European culture and society and assists people in their understandings of themselves in the past, present and future.

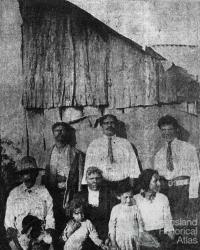

Berajondo

Berajondo is a small rural holding located about 50 kilometres northwest of Bundaberg in the traditional country of the Gooreng Gooreng Aboriginal people. 'Berajondo' is the name of the district and the name of the property. The property was selected in 1910 under the Land Act, by the grandfather of the current owners. For nearly a century, four generations of the Aboriginal family and their close kin have maintained an intimate connection with the property and the broader Gooreng Gooreng social landscape. Berajondo was a safe haven for Aboriginal people in the early twentieth century during a time when many persons were removed to reserves and missions under the provisions of the Aboriginal Protection and Restriction on the Sale of Opium Act 1897.

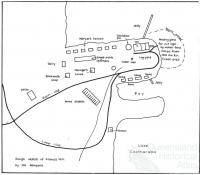

John Williams built the original homestead soon after he took ownership of the property. Some of his children also built smaller dwellings on the property, living there until the mid-1930s. After James, John’s son, inherited the property in the 1930s, he made several modifications to the homestead, which was lost to fire in late 1960s. Its replacement, the extant homestead, is a five-roomed vertical plank pine house that sits in virtually the same position as the original homestead, to one side of a large cleared paddock surrounded by open woodland forests, which extend to the property’s boundaries.

Social mapping of contemporary knowledge of the changing use of the property demonstrates that Berajondo is embedded in a wider cultural landscape linking the present to the past, documenting part of the continuous record of Aboriginal use and ownership of Gooreng Gooreng country. The shared experience of people with a connection to Berajondo creates a strong and tangible basis for maintaining and affirming a sense of collective social identity derived from this history, both as members of the extended family connected to Berajondo and as Gooreng Gooreng persons.

Mill Point

Mill Point is a sawmill settlement established on the shores of Lake Cootharaba at Elanda Point in 1869 to exploit the extensive timber resources of the hinterland and during its heyday employed over 200 men. They and their families made up a thriving community. A school, hotel, shops and other businesses supported the community. An extensive tramway system was constructed to bring timber from the hinterland to the mill, and boats carried the sawn timber down the lake and river system to Tewantin for shipment to Brisbane.

A cemetery was established with 43 burials recorded between 1873 and 1891, including nine men, four women and 30 children. The first burials included four of the five men who were killed in the boiler explosion of 29 July 1873, namely Charles Long, Patrick Tierney, Joseph White and Phelim Molloy. The fifth man, Patrick Molloy (brother to Phelim) was buried in the Gympie Cemetery after transport to Gympie Hospital for treatment of his severed foot as a result of the explosion. Children buried in the cemetery died of causes such as lung problems, wasting, thrush, convulsions and drowning. The mill closed in 1892 after exhausting local softwood resources. Dairy farmers moved into the area in the early twentieth century, but dairy farming was never really successful owing to the poor pasture available. The property changed ownership a number of times until it was transferred to the Queensland Government in 1983 and gazetted as part of Cooloola National Park in 1985.

Many hundreds of people, many from Scotland and England, worked in the mill over its short period of operation, moving between gold mining and sawmilling operations in southeast and central Queensland. Places like Mill Point are today important places where descendants interact with the landscapes that their forebears inhabited.

Australian poet Judith Wright visited the Mill Point cemetery and wrote a poem about life as she imagined it at the settlement during the late 1800s. The poem was written about the life of a man from the settlement known as Alfred Watt. In fact, Alfred was one of the first infants to be buried at the cemetery in 1874 at the tender age of four months and 20 days.

References and Further reading (Note):

E. Brown, Cooloola Coast : Noosa to Fraser Island: the Aboriginal and settlers histories of a unique environment, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2000

References and Further reading (Note):

D. James, ‘An Anangu ontology of place’, in F. Vanclay, M. Higgins and A. Blackshaw (eds) Making sense of place: exploring concepts and expressions of place through different senses and lenses. National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2008

References and Further reading (Note):

C. Pocock, ‘Blue lagoons and coconut palms: the creation of a tropical idyll in Australia’, The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 16/3, 2005

References and Further reading (Note):

D. Trigger, ‘Place, belonging and nativeness’, in F. Vanclay, M. Higgins and A. Blackshaw (eds) Making sense of place: exploring concepts and expressions of place through different senses and lenses. National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2008

References and Further reading (Note):

F. Vanclay, ‘Place matters’, in F. Vanclay, M. Higgins and A. Blackshaw (eds) Making sense of place: exploring concepts and expressions of place through different senses and lenses. National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2008

References and Further reading (Note):

J. Wright, ‘The graves at Mill Point’, The Bulletin, 77/3972, 1956

Date created:

29 November 2010 Copyright © Susan O’Brien, Sean Ulm, David Trigger, Michael Williams, 2010

Related:

Memory Alf Watt is in his grave

These eighty years.

From his bones a bloodwood grows

With long leaves like tears.

His girl grew weary long ago;

She’s long lost the pain

Of crying to the empty air

To hold her boy again.

When he died the town died.

Nothing’s left now

But the wind in the bloodwoods:

“Where did they go?

In the rain beside the graves

I heard their tears say

– This is where the world ends;

The world ends today.

Six men, seven men

Lie in one furrow.

The peaty earth goes over them,

But cannot blind our sorrow – ”

“Where have they gone to?

I can’t hear or see.

Tell me of the world’s end,

You heavy bloodwood tree.”

“There’s nothing but a butcher-bird

Singing on my wrist,

And the long wave that rides the lake

With rain upon its crest.

There’s nothing but a wandering child

Who stoops to your stone;

But time has washed the words away,

So your story’s done.”

Six men, seven men

Are left beside the lake,

And over them the bloodwood tree

Flowers for their sake.