- Home

- Quintessential Queensland

- Distinctiveness

- Perceptions

- Perceptions: how people understand the landscape

- From runs to closer settlement

- Geological survey of Queensland

- Mapping a new colony, 1860-80

- Mapping the Torres Strait: from TI to Magani Malu and Zenadh Kes

- Order in Paradise: a colonial gold field

- Queensland atlas, 1865

- Queensland mapping since 1900

- Queensland: the slogan state

- Rainforests of North Queensland

- Walkabout

- Queenslanders

- Queenslanders: people in the landscape

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape

- Australian South Sea Islanders

- Cane fields and solidarity in the multiethnic north

- Chinatowns

- Colonial immigration to Queensland

- Greek Cafés in the landscape of Queensland

- Hispanics and human rights in Queensland’s public spaces

- Italians in north Queensland

- Lebanese in rural Queensland

- Queensland clothing

- Queensland for ‘the best kind of population, primary producers’

- Too remote, too primitive and too expensive: Scandinavian settlers in colonial Queensland

- Distance

- Movement

- Movement: how people move through the landscape

- Air travel in Queensland

- Bicycling through Brisbane, 1896

- Cobb & Co

- Journey to Hayman Island, 1938

- Law and story-strings

- Mobile kids: children’s explorations of Cherbourg

- Movable heritage of North Queensland

- Passages to India: military linkages with Queensland

- The Queen in Queensland, 1954

- Transient Chinese in colonial Queensland

- Travelling times by rail

- Pathways

- Pathways: how things move through the landscape and where they are made

- Aboriginal dreaming paths and trading ways

- Chinese traders in the nineteenth century

- Introducing the cane toad

- Pituri bag

- Press and the media

- Radio in Queensland

- Red Cross Society and World War I in Queensland

- The telephone in Queensland

- Where did the trams go?

- ‘A little bit of love for me and a murder for my old man’: the Queensland Bush Book Club

- Movement

- Division

- Separation

- Separation: divisions in the landscape

- Asylums in the landscape

- Brisbane River

- Changing landscape of radicalism

- Civil government boundaries

- Convict Brisbane

- Dividing Queensland - Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party

- High water mark: the shifting electoral landscape 2001-12

- Hospitals in the landscape

- Indigenous health

- Palm Island

- Secession movements

- Separate spheres: gender and dress codes

- Separating land, separating culture

- Stone walls do a prison make: law on the landscape

- The 1967 Referendum – the State comes together?

- Utopian communities

- Whiteness in the tropics

- Conflict

- Conflict: how people contest the landscape

- A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest

- Battle of Brisbane – Australian masculinity under threat

- Dangerous spaces - youth politics in Brisbane, 1960s-70s

- Fortress Queensland 1942-45

- Grassy hills: colonial defence and coastal forts

- Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891

- Iwasaki project

- Johannes Bjelke-Petersen: straddling a barbed wire fence

- Mount Etna: Queensland's longest environmental conflict

- Native Police

- Skyrail Cairns (Research notes)

- Staunch but conservative – the trade union movement in Rockhampton

- The Chinese question

- Thomas Wentworth Wills and Cullin-la-ringo Station

- Separation

- Dreaming

- Imagination

- Imagination: how people have imagined Queensland

- Brisbane River and Moreton Bay: Thomas Welsby

- Changing views of the Glasshouse Mountains

- Imagining Queensland in film and television production

- Jacaranda

- Literary mapping of Brisbane in the 1990s

- Looking at Mount Coot-tha

- Mapping the Macqueen farm

- Mapping the mythic: Hugh Sawrey's ‘outback’

- People’s Republic of Woodford

- Poinsettia city: Brisbane’s flower

- The Pineapple Girl

- The writers of Tamborine Mountain

- Vance and Nettie Palmer

- Memory

- Memory: how people remember the landscape

- Anna Wickham: the memory of a moment

- Berajondo and Mill Point: remembering place and landscape

- Cemeteries in the landscape

- Landscapes of memory: Tjapukai Dance Theatre and Laura Festival

- Monuments and memory: T.J. Byrnes and T.J. Ryan

- Out where the dead towns lie

- Queensland in miniature: the Brisbane Exhibition

- Roadside ++++ memorials

- Shipwrecks as graves

- The Dame in the tropics: Nellie Melba

- Tinnenburra

- Vanished heritage

- War memorials

- Curiosity

- Curiosity: knowledge through the landscape

- A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

- Duboisia hopwoodii: a colonial curiosity

- Great Artesian Basin: water from deeper down

- In search of Landsborough

- James Cook’s hundred days in Queensland

- Mutual curiosity – Aboriginal people and explorers

- Queensland Acclimatisation Society

- Queensland’s own sea monster: a curious tale of loss and regret

- St Lucia: degrees of landscape

- Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo

- Imagination

- Development

- Exploitation

- Transformation

- Transformation: how the landscape has changed and been modified

- Cultivation

- Empire and agribusiness: the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company

- Gold

- Kill, cure, or strangle: Atherton Tablelands

- National parks in Queensland

- Pastoralism 1860s–1915

- Prickly pear

- Repurchasing estates: the transformation of Durundur

- Soil

- Sugar

- Sunshine Coast

- The Brigalow

- Walter Reid Cultural Centre, Rockhampton: back again

- Survival

- Survival: how the landscape impacts on people

- Brisbane floods: 1893 to the summer of sorrow

- City of the Damned: how the media embraced the Brisbane floods

- Depression era

- Did Clem Jones save Brisbane from flood?

- Droughts and floods and rail

- Missions and reserves

- Queensland British Food Corporation

- Rockhampton’s great flood of 1918

- Station homesteads

- Tropical cyclones

- Wreck of the Quetta

- Pleasure

- Pleasure: how people enjoy the landscape

- Bushwalking in Queensland

- Cherbourg that’s my home: celebrating landscape through song

- Creating rural attractions

- Festivals

- Queer pleasure: masculinity, male homosexuality and public space

- Railway refreshment rooms

- Regional cinema

- Schoolies week: a festival of misrule

- The sporting landscape

- Visiting the Great Barrier Reef

By:

Trish FitzSimons From the air, the braided Channel Country constitutes some of the most distinctive landscape in Australia. Essentially a desert that floods, the Channel Country’s fascinating history is intricately connected to its geography. Its prehistory as part of an inland sea and its current ecosystem of pulses of water mean that it has been precious land to pastoralists, to Aboriginal people and now to companies dedicated to the exploitation of oil and gas reserves. Like the Murray Darling system it extends across several states, but unlike it, the Channel Country has never been harnessed.

The Channel Country of Queensland comprises a quarter of the state, at the ABS Census of 2006 had less than 1400 inhabitants, and has been at the centre of several of the defining historical events, cultures and industries of the state. Aboriginal trade routes crossing the continent from north to south followed its rivers and goods traded ended up across a huge area of central and northern Australia. Burke and Wills died in its midst in 1861, having used it as a base for their expedition to the Gulf of Carpentaria, the first South to North crossing of the continent by non-Aboriginal people. It was the base of the pastoral fortune of families such as the Duracks. It is at the heart of the pastoral empire of S. Kidman and Co, the largest landowner in the Channel Country. The Cooper Basin Oil and Gas fields are centred in its south-western corner. And in the era since the Mabo and Wik decisions of Australia’s High Court opened the possibility of legal recognition of native title, it is the site of multiple, sometimes overlapping claims. To understand this complex history it is necessary to understand the Channel Country’s distinctive geography.

Slow, shallow water

Anne Kidd, who has lived there all her adult life, said in 2000:

Channel Country to me is where a lot of the country is inundated by slow, shallow water. It can make the difference between a good season and a bad season. If you don’t get a flood … you’re going to have a bad time. If you do get a flood, you’re home and hosed.

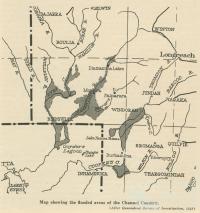

It is an extremely flat and ancient landscape of sand dunes and river channels formed by the movement of water and wind. Yet it more than meets the definition of a desert, averaging only 150 mm annual rainfall, with huge variation year to year. When rain does come it spreads out into myriad ‘braided channels’ that provide moisture and alluvial nutrient to the area. Edith McFarlane, who lived in the Channel Country from the 1920s to the 1950s, explained what the Channel Country was like at Tanbar Station:

When the channels really flooded we had sixty miles of water from east to west. And because it's a very low gradient down to Lake Eyre, the water moves very slowly and spreads out. In dry seasons that flooded ground cracks. In a long dry period, a horse could stumble into a crack and break its leg.

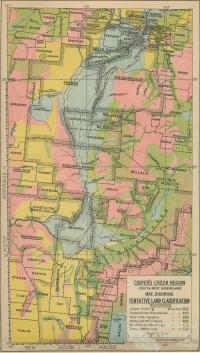

Queensland’s Channel Country is the source of most of the water in the Lake Eyre Drainage basin, the river system west of the Murray-Darling that takes up approximately one sixth of the Australian landmass. This basin extends into the Northern Territory and South Australia, with one edge in New South Wales. The key rivers of the Channel Country – the Georgina, the Diamantina and Cooper Creek – drain the land from far to the north and as a result have permanent waterholes. Only rarely, however, is there a big enough pulse of water to make it through to Lake Eyre. The rest of the water evaporates or fills the cracked ground and channels. Although it is generally a dry salt pan, Lake Eyre is the remnant of an inland sea. Unlike the Murray-Darling system to its east, the Channel Country has never been cultivated, dammed or irrigated.

Isabel Tarrago, an Aranta woman born on the Georgina River in the Channel Country said in 2000 that the Georgina, although a desert landscape,

never dries … it’s a significant place for pastoralists because it’s always the watering hole for their stock. But it was also significant for us because it was our survival. We travelled the Georgina to do our ceremonies, and where there’s water there’s food. So it is a pathway of two cultures.

Every nook and corner

Permanent waterholes and periodic pulses of substantial water allowed Aboriginal people to live in great numbers in the Channel Country, presumably varying according to the shifting weather patterns. Accurate population counts prior to and immediately following European occupation are non-existent, and eyewitness accounts vary. The explorer John McKinlay, who traveled through in 1861 looking for Burke and Wills, noted that Aboriginal people ‘seemed to pour out from every nook and corner where there was water’. The Channel Country was at the heart of an extensive network of trade routes and dreaming pathways that linked this part of the land with the rest of the continent. Pituri, stone, ochre and pearl shells were traded. Pituri is a woody bush whose main area of growth is around the sandhills of the central Georgina River near Bedourie. When specially ground and prepared, its leaves and stems have a ‘psycho-active’ effect and were used in ceremonies and in hunting.

Channels of exploration

The unusual structure of inland waterways and the existence of well-worn Aboriginal tracks, as well as in several instances Aboriginal guides and informants, partly contributed to a succession of explorers traveling through the Channel Country in the middle of the nineteenth century. Charles Sturt (1844-45) Augustus Gregory (1858), Thomas Mitchell (1846), Burke and Wills (1860-61), John McKinlay (1861) and William Hodgkinson (1861, 1877) were variously looking for an inland sea long gone; looking for pastoral land; looking for territorial advantage for the states that had sponsored their trips. These expeditions opened up the possibility of pastoralism in the Channel Country, and in 1862 the Queensland government was successful in having their border extended westwards from 141 degrees to 138 degrees longitude.

Cattle kings

From 1868 pastoralists had ‘squatted’ in the Channel Country, beginning with the most fertile land around Cooper Creek and the Diamantina River. These included the Durack family who established themselves as major landowners in the Channel Country before selling their leases and moving on to the Kimberley. In the period after initial occupation, but before the pastoralists’ hold on the land was secure, there was a great deal of conflict over Channel Country lands. In Mary Durack’s account of her family’s pioneering she wrote that by 1874-75 “many settlers now openly declared Western Queensland could only be habitable for whites when the last of the blacks had been killed out ‘by bullet or by bait’”.

Sheep were very common in the Channel Country but soon after the turn of the twentieth century the ravages of the 1890s drought and attacks by dingoes saw cattle take over from wool and lamb as the major pastoral products of the region. In the twentieth century Channel Country pastoralism came to be dominated by large companies owning multiple properties, although there are some smaller occupiers. The largest company was begun by Sidney Kidman (‘The Cattle King’) in 1899. In 2009 the company owned around 1.5 % of the landmass of Australia, with the bulk of their properties in the Channel Country. The essence of Kidman’s method was to move stock around according to the seasons, with droving between stations and to market essential before the advent of road-trains. Pastoral stock-routes largely followed the same north/south orientation as the rivers and Aboriginal pathways. During the World War I, Laura Duncan, pastoralist of Mooraberrie Station, battled the Queensland government for the right to sell her stock in Brisbane rather than Adelaide.

Aboriginal labour

After an initial period of intense conflict many Aboriginal people became imbricated in Channel Country pastoralism and were central to its continued success. Laura Duncan’s daughter Alice recalled in her memoir Where Strange Gods Call (1968) that ‘in those early days we relied almost entirely on aboriginal labour for everything’. Gradually, however, successive transformations first by cars and trucks, and later by planes and helicopters, changed pastoralism. By the time Aboriginal pastoral workers achieved equal pay in the late 1960s most Aboriginal people in the Channel Country had ceased to live on their traditional lands, or even nearby.

Authority to prospect and right to negotiate

The inland sea whose vestiges created the distinctive Channel Country geography also left a legacy of carboniferous deposits in the form of oil and gas. Since 1959 a series of oil and gas deposits have been found in the Cooper Basin of Queensland and South Australia (the eastern section of the Lake Eyre basin) that have been increasingly exploited by a several companies, of whom Santos is the largest. As the pace of discovering new sources of oil globally has slowed, and the rate of flow from existing wells has lessened, these natural resources have become increasingly valuable. Exploitation of these resources, based on an ‘authority to prospect’ co-exists with pastoralism, often sharing resources such as roads and fences. Since the landmark High Court decisions of Mabo (1992) and Wik (1996) native title is a third form of coexisting tenure in the Channel Country.

The Channel Country is home to at least eighteen different Aboriginal nations, many of whom are engaged in negotiating native title rights with the Federal government, with mining companies and with pastoralists. A legacy of the complex history of Aboriginal people in the Channel Country is that in many instances native title determinations have been held up by overlapping claimant groups. Although no native title claims in the Channel Country have been finally determined many Aboriginal groups are ‘registered native title claimants’ who hold a ‘right to negotiate’ in relation to oil and gas exploration and exploitation. Whatever the outcome the Channel Country’s history continues to be dominated by its distinctive landscape.

Copyright © Trish FitzSimons, 2010

Related:

Distinctiveness